NATIONAL IRRIGATION PLAN H-2008

1 Justification for a National Irrigation Plan

1.1 Historical background of irrigation policy in Spain

Historically, irrigation has been linked to the development of agriculture in the great Mediterranean civilizations. In Spain, irrigation was introduced and widely developed centuries ago to take advantage of the natural light and heat conditions of the Mediterranean basin, and there are numerous historical references to the promotion of irrigation.

However, state intervention in irrigation development has its contemporary origins in the late 19th century, driven by the Regenerationist movement. It was precisely this school of thought that elevated water policy to the status of a central policy and a fundamental element for overcoming Spain's economic backwardness. This water policy was to be understood broadly as an accelerated process of transformation from extensive and traditional agriculture to intensive and modern agriculture through irrigation.

The general canal plan advocated by Joaquín Costa was the ideological basis of the first National Plan of Hydraulic Works drafted by Gasset in 1902. This Plan assigned the construction and financing of hydraulic works to the State, thus marking itself as the spearhead of state interventionism in irrigation policy that would culminate in the Law of 1911 still in force.

During the first decades of the 20th century, and especially under the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera, water policy underwent significant development under the Count of Guadalhorce, who is also credited with creating the Hydrographic Confederations, a model of organization, planning and participation in water management whose most original element is the definition of the hydrographic basin as the basic unit of action.

Costa's ideas found in Lorenzo Pardo the water expert who, in the Ebro Basin, as head of the Hydrographic Confederation, translated the ideological principles of regenerationism into technical projects and construction works. However, what truly cemented Pardo's position as a pioneer of modern hydrological planning in Spain was the drafting of the 1933 National Plan for Hydraulic Works. Until then, all hydraulic works plans had been mere catalogs of more or less coherent projects, whereas the 1933 Plan presented an integrated vision of hydrological planning.

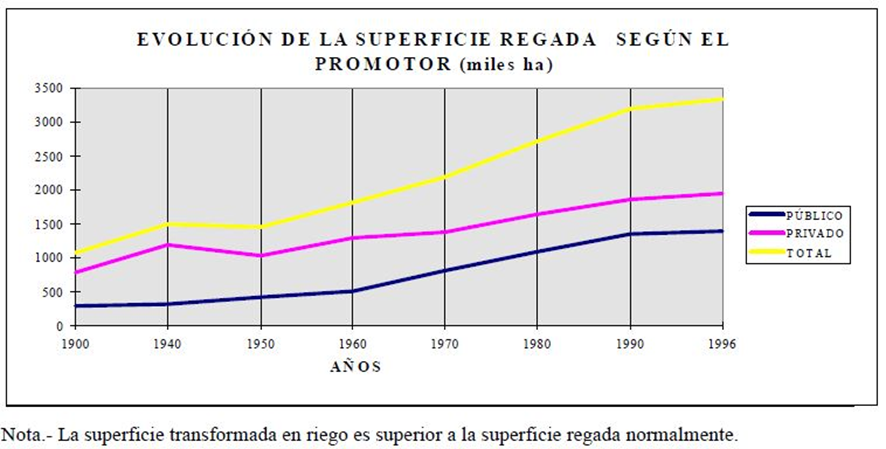

In 1939, the National Institute of Colonization (INC) was created, and the Law for the Colonization of Large Areas was passed. At this time, irrigation policy became linked to colonization policy, whose fundamental objective was the settlement of colonists on lands expropriated in the Large Irrigated Areas developed by the State. The 1939 Law intended that the planning and execution of colonization projects would be carried out in collaboration between the INC and private enterprise. The application of this law was largely unsuccessful, as this collaboration never materialized. Consequently, in the 1940s, public irrigation development was almost nonexistent, barely reaching 20,000 hectares, precisely at a time when food shortages were a serious problem and the need to increase agricultural productivity was imperative (the period of autarky). In contrast, the Law of Reserves was far more successful, allowing for a significant expansion of irrigation based on private development. Nearly 100,000 hectares were transformed through this law in just a few years of the 1940s.

The Colonization Law of 1939 gave way to the Law of Large Irrigated Areas of 1949, still in force, which entailed total state intervention in large-scale irrigation projects. According to the new law, the state decided which large areas would be developed, promoted the development, and carried out and financed all the necessary works and investments. The application of the new law, along with a significant budget allocation for the public development of irrigation systems, bore fruit in the 1950s and even more so in the 1960s, when irrigation policy became the key policy for modernizing agriculture and increasing and diversifying food production during a period of strong economic growth and dietary changes. The budget allocated to irrigation policy reached its peak in that decade, within the framework of the Development Plans. Thus, in the 1950s, 192,000 hectares were transformed by public initiative, and in the 1960s, nearly 350,000 hectares.

In the 1970s, the pace of irrigation development remained high, before beginning a slow decline in the 1980s that intensified in the 1990s, largely due to budget constraints. In the mid-1980s, irrigation development became the responsibility of the regional governments, although the central government retained jurisdiction over Irrigated Areas of National Interest. Despite the financial contributions of both levels of government, the total budget allocated to irrigation decreased significantly from that point onward, leading to a sharp drop in the rate of development.

Government support for private irrigation conversion has been another constant feature of Spanish irrigation policy, primarily affecting systems whose conversion was easy and inexpensive, most of them well-fed. This policy began in the 1940s with the reserve system (compensatory prices) and continued in subsequent decades with other incentives (subsidies, soft loans, tax breaks, technical assistance, and others). It can be said that a significant portion of privately owned irrigation systems have benefited from this type of support to undertake the conversion.

In summary, the balance of public irrigation transformation throughout the 20th century is as follows: 316,000 hectares transformed through the 1911 Law, 992,000 hectares through the 1949 Law (later consolidated into the 1973 Law on Agrarian Reform and Development), and 95,000 hectares through initiatives by the Autonomous Communities. To these figures should be added the 695,000 hectares converted to irrigated land by private initiatives with public subsidies, representing a significant percentage of the total of almost 1,300,000 hectares transformed by private initiatives. Few countries can boast such a record of results, reflecting the importance that Spanish economic and agricultural policies have historically placed on irrigation.

1.2 The importance of irrigation in Spain

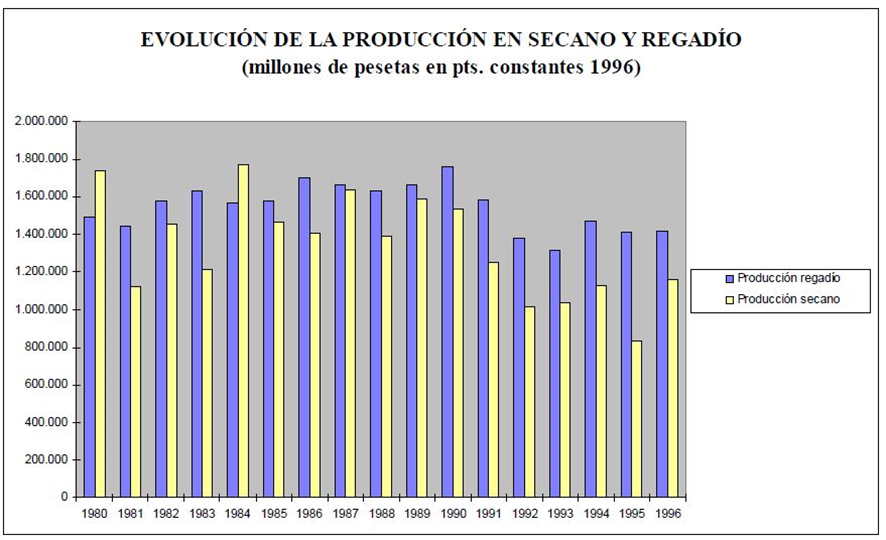

Irrigation has played a key role in the Spanish agricultural economy, especially since 1940. During the years of food rationing (the period of autarky), irrigation, transformed by private initiative through the policy of reserves, improved the supply of basic foodstuffs such as sugar, potatoes, and cereals. In the 1950s, when Spanish agriculture began its economic takeoff, irrigation became at the forefront of the agricultural modernization process. It was precisely in irrigated agriculture that the use of modern means of production took hold most strongly, where the substitution of labor by capital occurred most intensely, and where agricultural productivity increased most rapidly.

But perhaps the period in which irrigation played the most decisive role was the economic development of the 1960s. Rapid economic growth and a sharp increase in per capita income led to a shift in the Spanish diet, with a decrease in the consumption of some foods (cereals and legumes) and an increase in others (sugar, meat, milk, vegetable oils, fruits, and vegetables). The agricultural production imbalances of those years (production exceeding consumption and consumption exceeding production) caused inflationary pressures and a growing imbalance in the agricultural trade balance. The significant public reforms in irrigation during the 1960s provided an opportunity to overcome this situation, since the diversification of production afforded by irrigation made it possible to meet the new food demands of a more urbanized population with greater purchasing power than that of the 1940s and 50s.

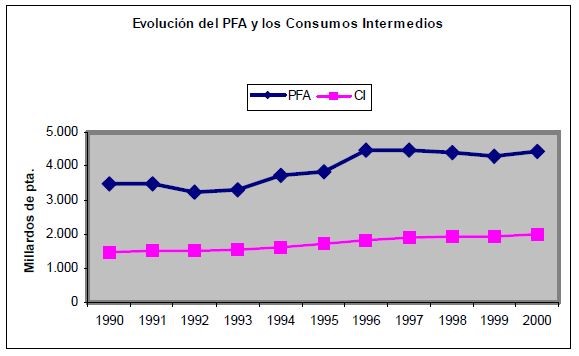

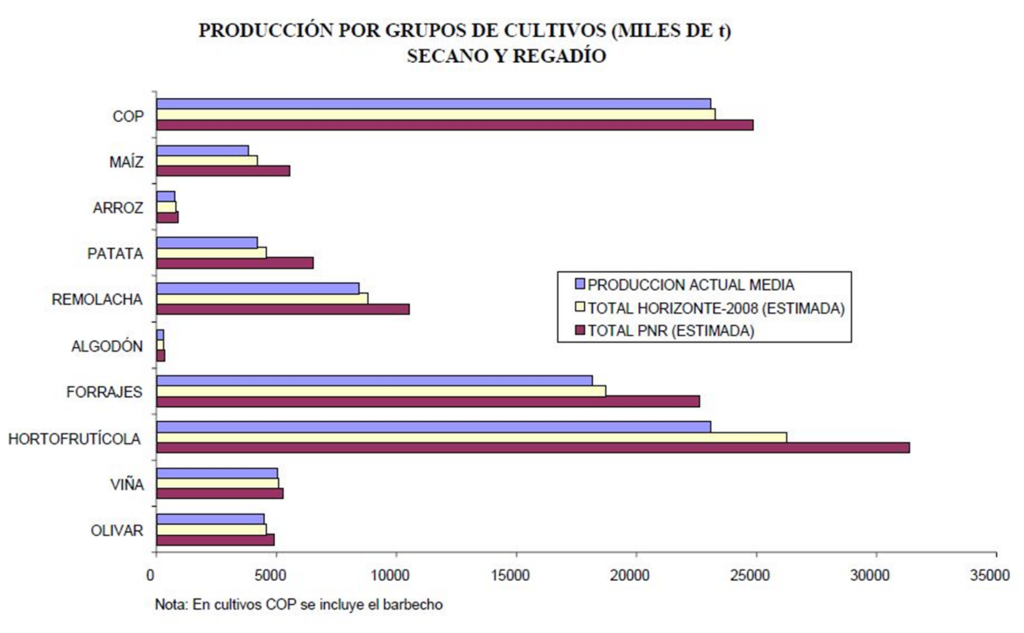

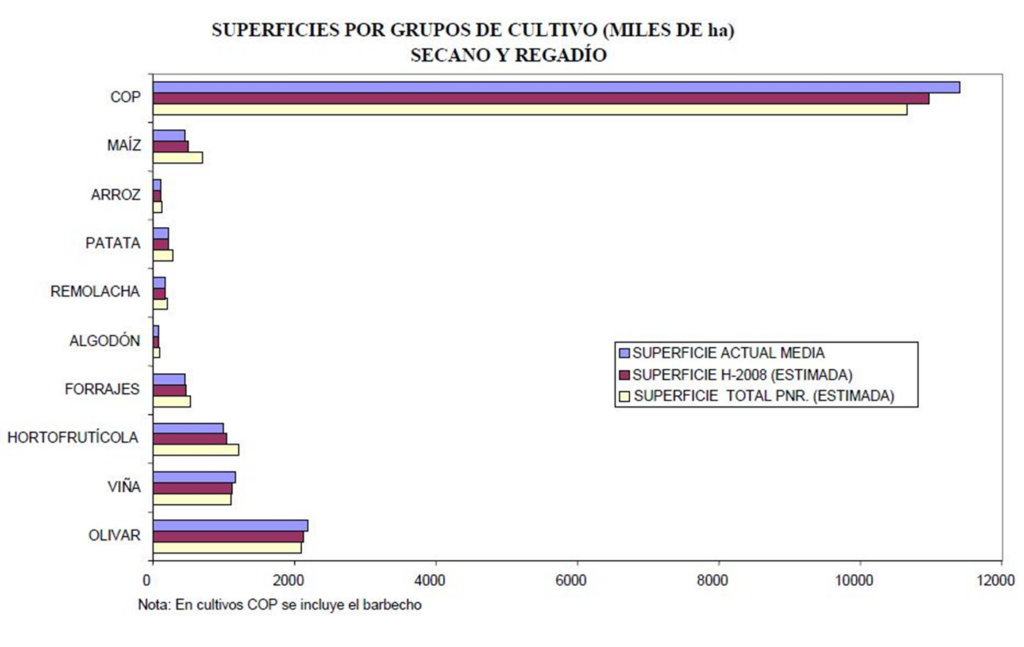

In subsequent years, irrigation continued to play a key role in the mature phase of the agricultural modernization process. Thanks to the increased agricultural productivity generated by irrigation, a shrinking agricultural workforce has been able to feed a growing and increasingly demanding urban population in terms of the variety, quantity, and quality of food it requires. As a result of the proactive irrigation policy, the final agricultural output currently contributed by irrigated Spanish production accounts for more than 501,000 tons of total final agricultural output, while irrigated land occupies only 131,000 tons of usable agricultural land.

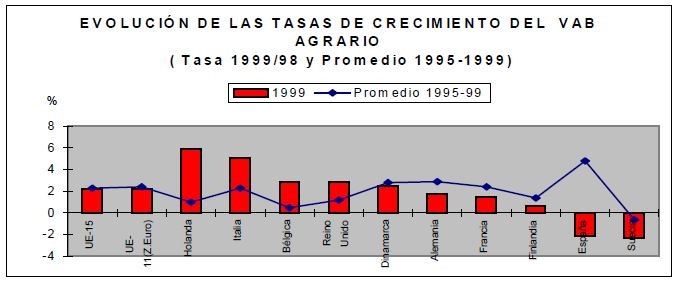

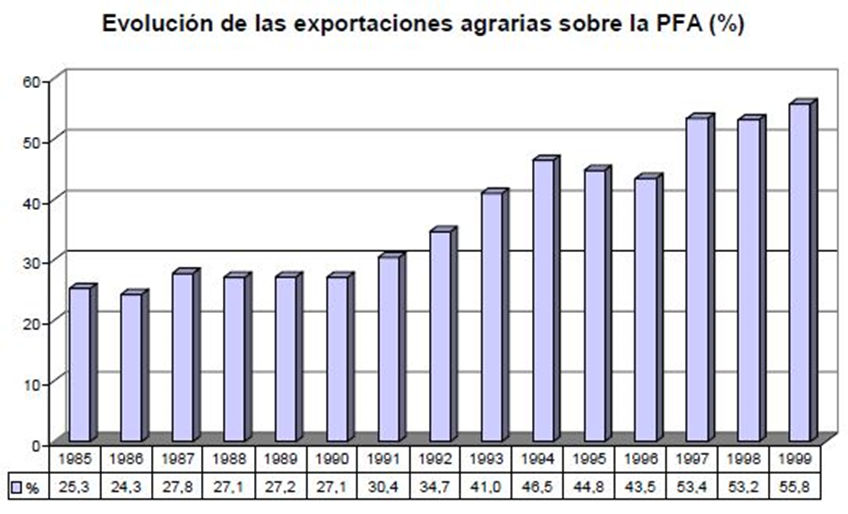

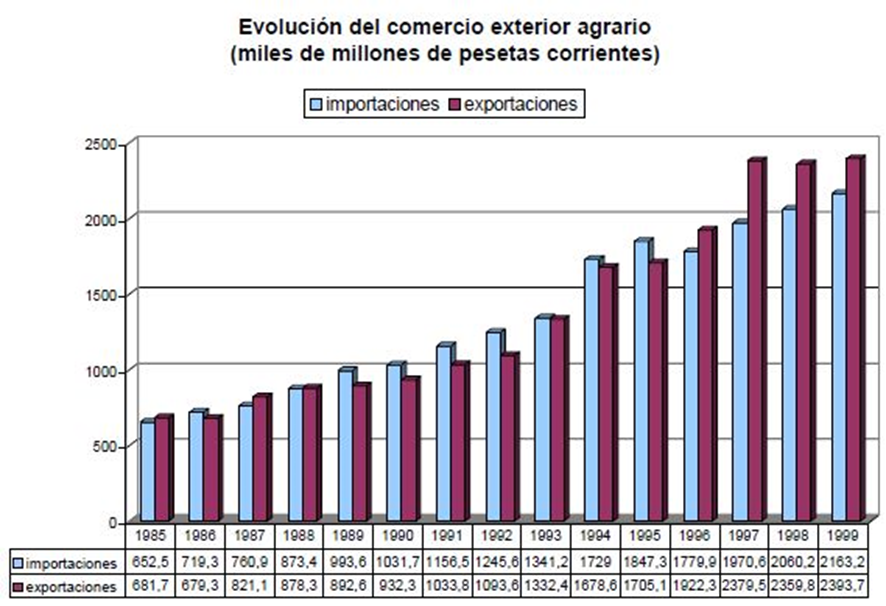

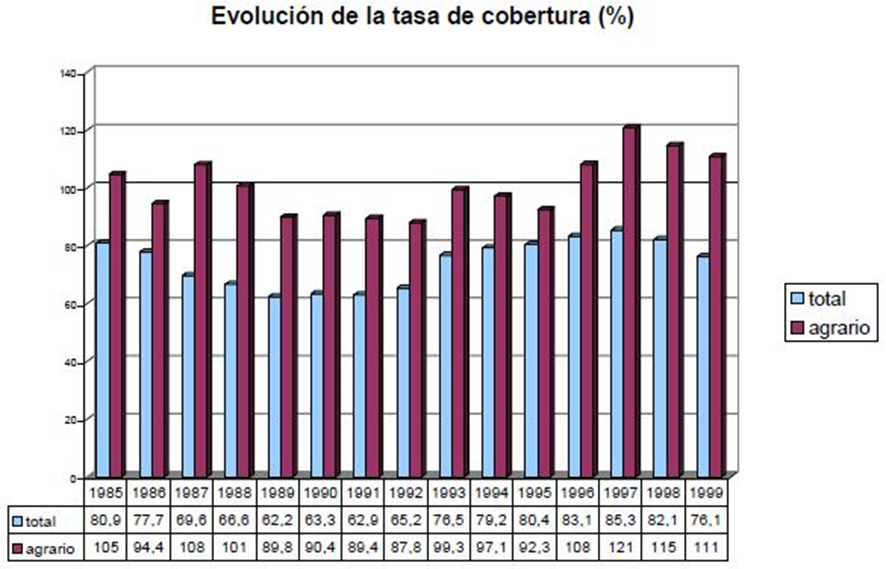

At the same time, irrigation has contributed to the shift in the trade balance from a deficit in the 1960s, 70s, and part of the 80s to a surplus in the 1990s. Irrigation has been crucial in making the supposed advantages that some agricultural products offered in a scenario of joining the EEC a reality. Thus, once the export restrictions established for the transitional period were overcome, the significant surge in the agricultural trade balance during the second half of the 1990s was mainly due to the strong expansion of exports of irrigated products, and especially fruits and vegetables. Therefore, irrigation is partly responsible, along with other factors, for the agricultural trade balance going from a coverage rate of 82% in 1985 to one of 110% in 1999, and for the percentage of exports on Final Agricultural Production going from representing 30% to 56% in the same period.

But the importance of irrigation in the Spanish agricultural economy is not only relevant from a macroeconomic perspective, as we have just seen, but also from a microeconomic one. Indeed, the conversion to irrigated land, whether public or private, has meant economic survival for many farmers. Given the structural problems of Spanish agriculture, characterized by the small size of farms, many farmers have been able to increase their production and agricultural income thanks to irrigation. Sometimes, converting all or part of the farm to irrigated land has been the only way to remain in agriculture. This is especially true for small-scale private conversions, often carried out with public subsidies, which have allowed for the irrigation of part of the farm through wells or direct intakes from surface water sources.

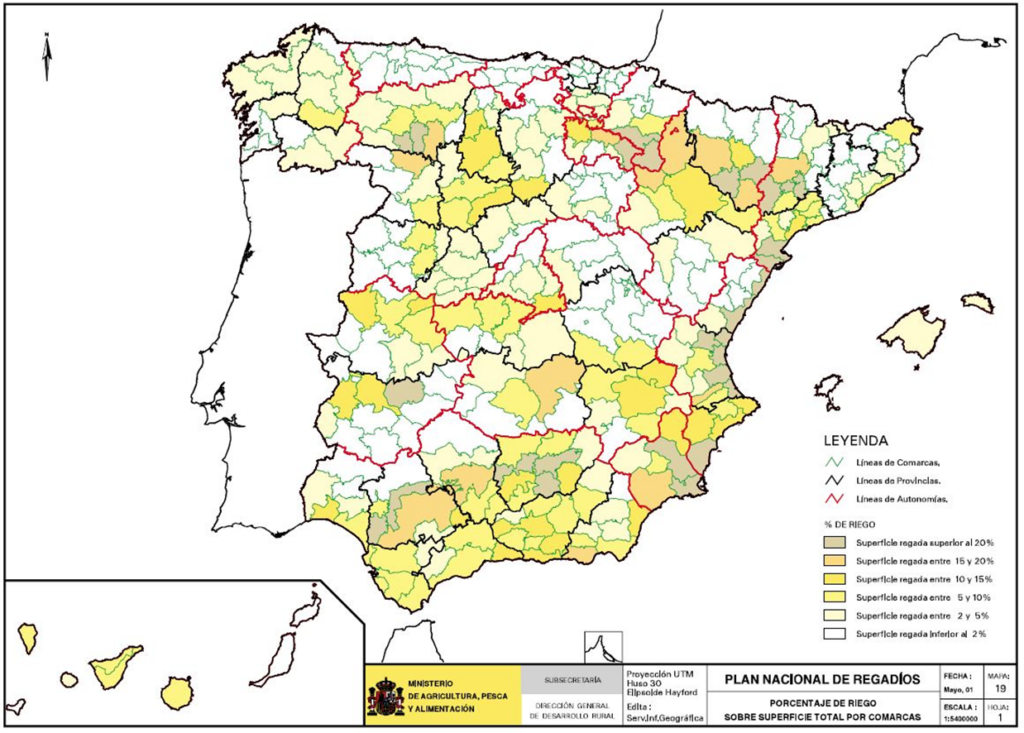

To understand the contribution of irrigation at the farm level, it suffices to say that, on average, one hectare of irrigated land produces six times more than one hectare of dryland and generates four times the income. In the intensively irrigated areas of the Mediterranean and southern Atlantic coasts, these differences are much greater, which explains the strong expansion of private irrigation over the last 25 years. In contrast, in the irrigated areas of inland Spain, the impact of public transformations carried out since the 1940s is much greater. But irrigation not only allows for a higher income but also a more secure one. This is due to two factors: firstly, the greater diversification of production that irrigation allows, thus avoiding the risk of dryland monoculture; and secondly, it reduces the climate risk of arid and semi-arid drylands, where the variability of annual and seasonal rainfall causes severe economic losses.

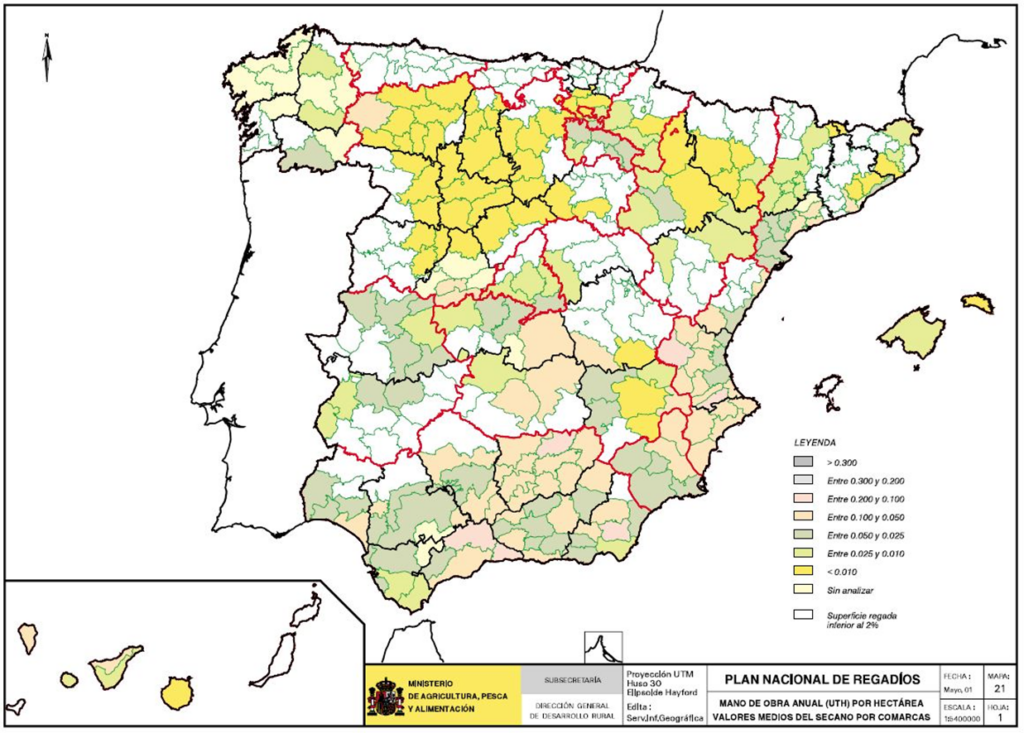

If we now analyze the contribution of irrigation from the perspective of rural development, the figures are equally telling. One of the main objectives of rural development policy is job creation and retaining the rural population, and irrigation makes a decisive contribution to achieving this goal. The primary contribution of irrigation is its greater generation of direct employment, since on average one hectare of irrigated land requires 0.141 ATUs (Annual Work Units), while one hectare of dryland only needs 0.037 ATUs. Therefore, the average workforce potential of irrigated land is more than three times that of dryland farming. These differences are much greater in the agriculture of the Mediterranean and southern Atlantic coasts, where one hectare of irrigated land generates up to 50 times more employment than one hectare of dryland.

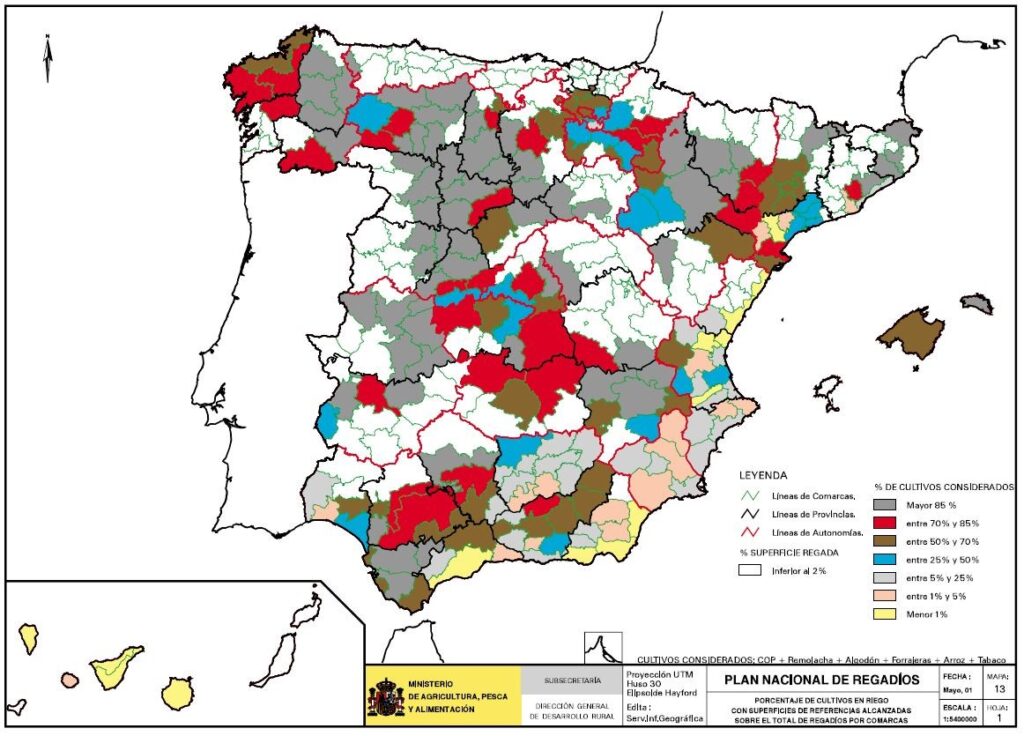

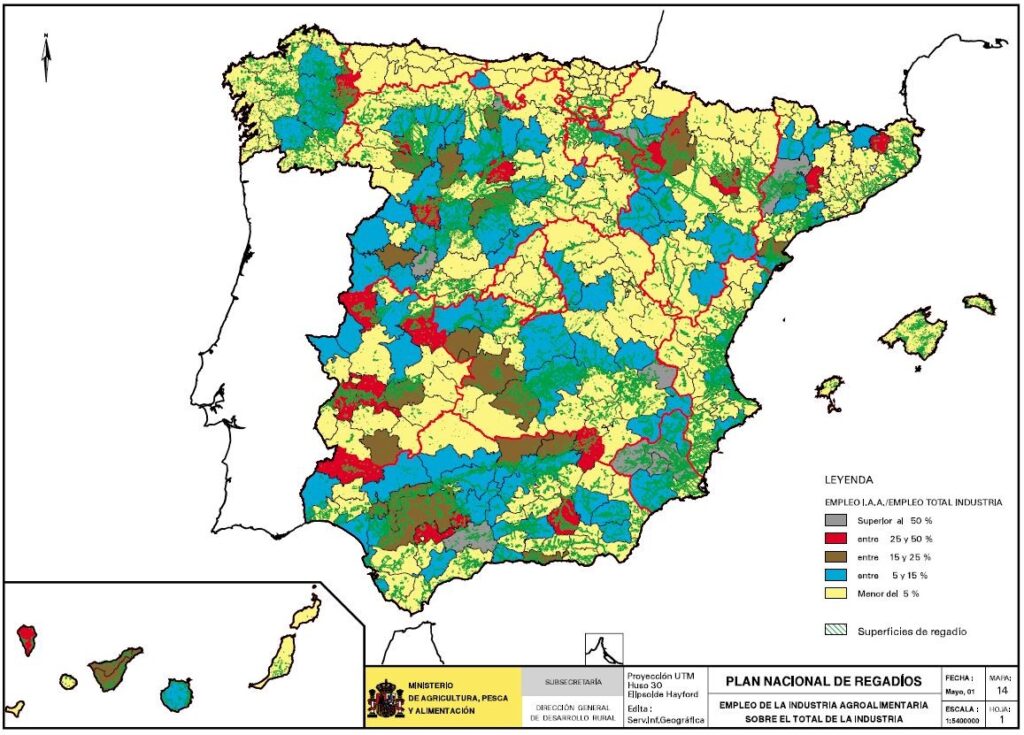

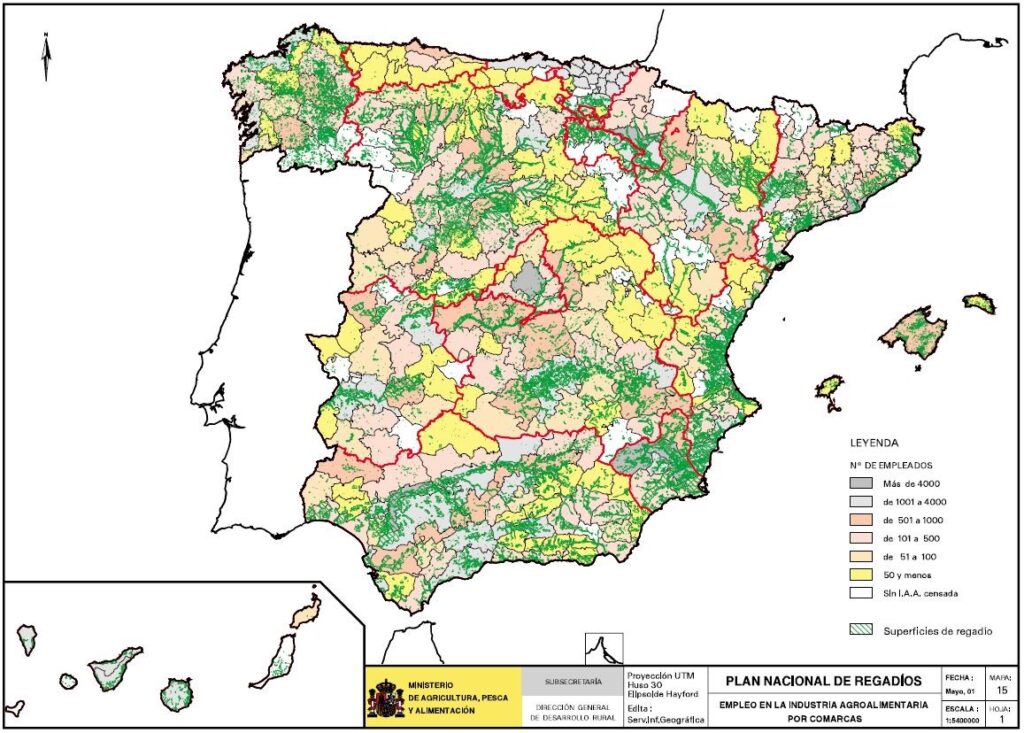

However, the direct employment generated by irrigation is neither the only nor, often, the main contribution of irrigation to rural development. Indeed, a substantial part of the primary processing agri-food industry is located near the agricultural raw material production centers in order to reduce transport costs and losses, as well as to guarantee the supply of processing plants. This is the case for the sugar industry, dehydrated animal feed, fruits and vegetables, potatoes, cotton, tobacco, and other products. But many of these products are grown in the continental and Mediterranean irrigated areas of our country, so irrigation generates a high level of employment in the agri-food industries that rely on the produce from the surrounding irrigated areas.

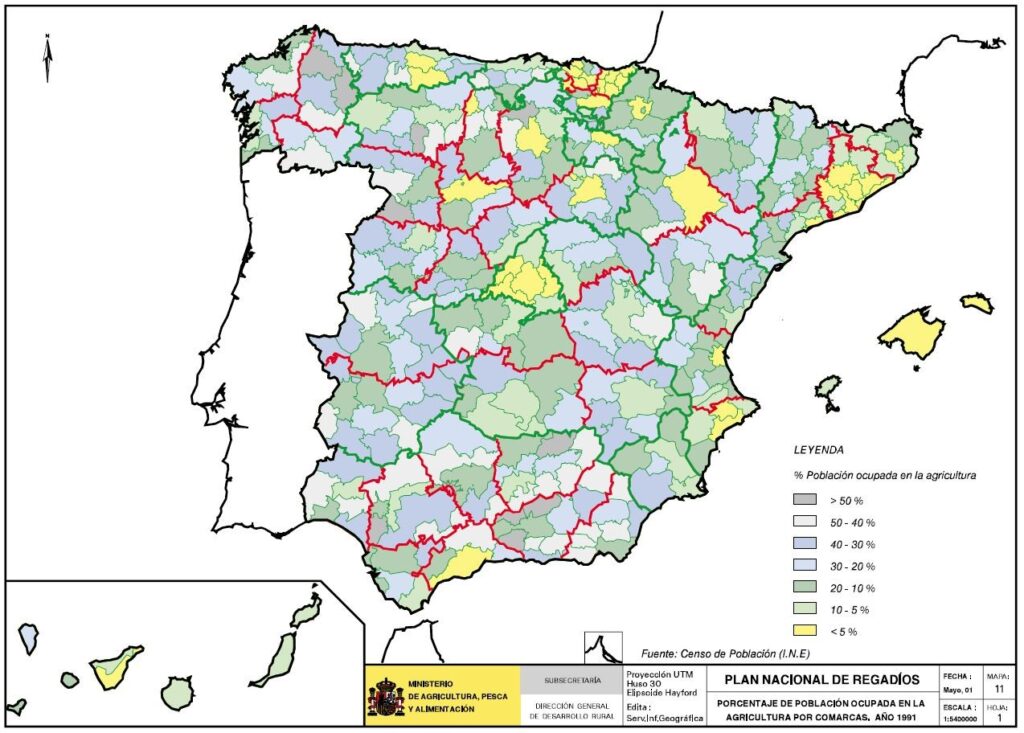

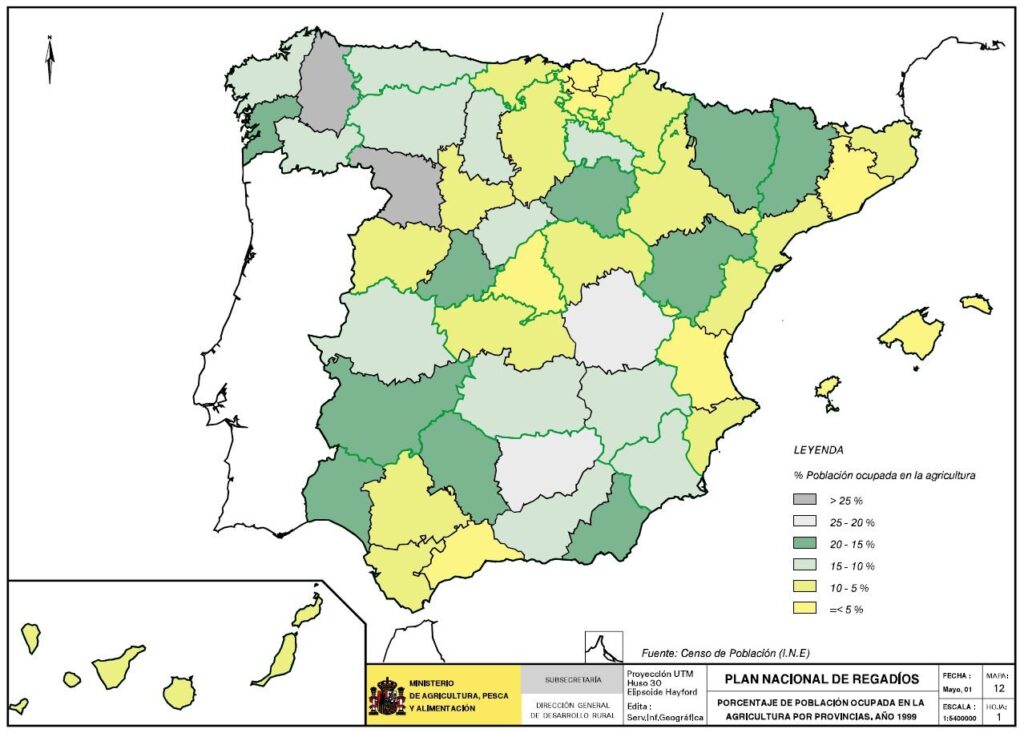

Therefore, areas with extensive irrigation often have high levels of employment in the agricultural and agri-food sectors, ranging from 20% to 40% of the total employed population. This is particularly evident in areas with intensive irrigation (the Ebro Valley, Murcia, the Valencian Community, and the Andalusian coast), but it can also be observed in other inland areas of Andalusia and in the large irrigated areas of Autonomous Communities such as Castile and León and Extremadura.

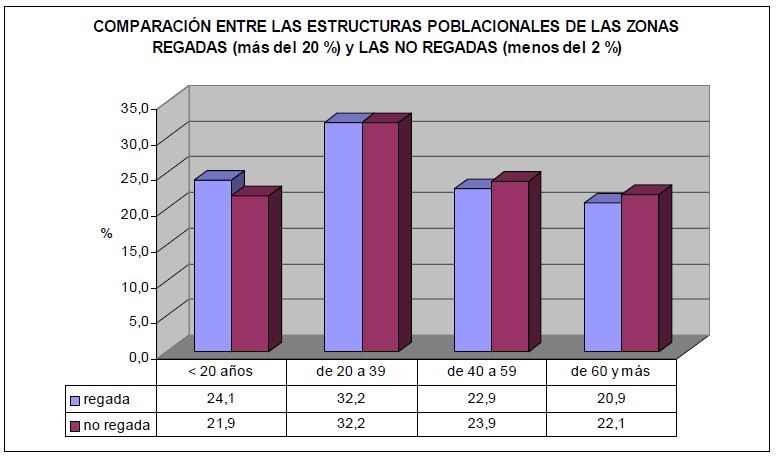

In many rural areas, not only coastal but also inland, irrigation has fostered a significant agri-food sector, playing a key role in generating income and employment in rural communities. The economic and social fabric supported by this sector has kept these rural areas alive, resulting in higher population density, a younger population, lower unemployment rates, and higher activity levels. Comparing the demographic and occupational structure of inland rural areas with and without irrigation reveals striking results regarding the importance of irrigation as a driving force for rural development. It is no surprise that in these areas there continues to be strong social demand for improving existing irrigation systems or even expanding irrigated land, as experience demonstrates that irrigation is a key element for maintaining the rural population.

Another element to consider when assessing the importance of irrigation is its role in rural land management. The irregular rainfall, typical of a Mediterranean climate, the low flow of rivers, a consequence of small basins, and the predominance of a territorial model based on an agricultural economy, spatially organized into numerous poorly connected rural settlements, meant that in most of Spain, the availability of water for irrigation has historically been the essential difference between the wealthiest and most underdeveloped rural areas, and the fundamental aspiration of all regions as a lever for improving their relative position and quality of life.

The establishment or presence of irrigation systems generates an activity that occupies space within the territory and is therefore conditioned by its characteristics, while simultaneously transforming that space. In this sense, irrigation fulfills a social function as a factor in territorial balance. Indeed, irrigation can curb rural exodus from areas at risk of abandonment or at least population loss, and, as has been demonstrated in some transformed areas, it has even acted as an element of demographic recovery. Thus, irrigation contributes to maintaining a certain territorial balance by retaining population in the area, which in declining rural areas is a fundamental objective to prevent abandonment and the consequent degradation of the land, landscape, natural resources, and environment.

Thus, multifunctional irrigation, characterized by its ability to retain population, organize land use, and maintain rural areas, can be considered a fundamental component of the new European agricultural model enshrined in Agenda 2000. This multifunctional irrigation is defined in the current National Irrigation Plan as social irrigation, and it deserves public support for the important services it provides to society as a whole.

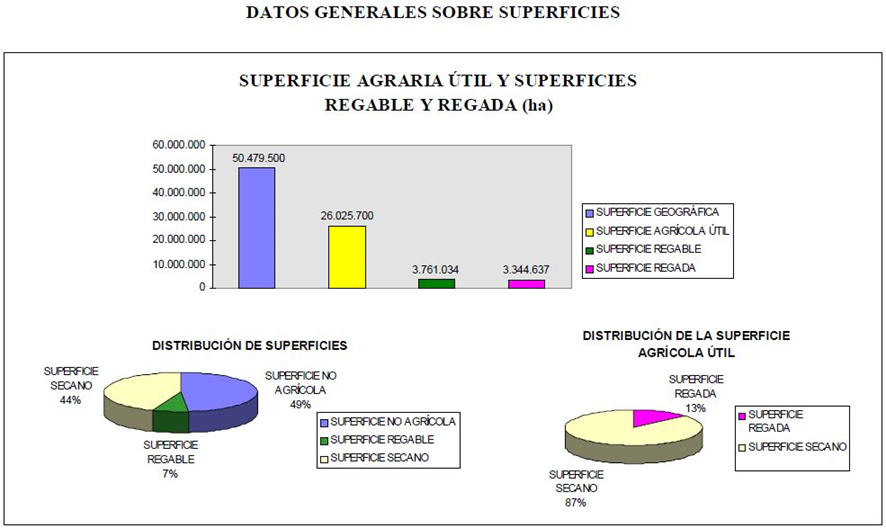

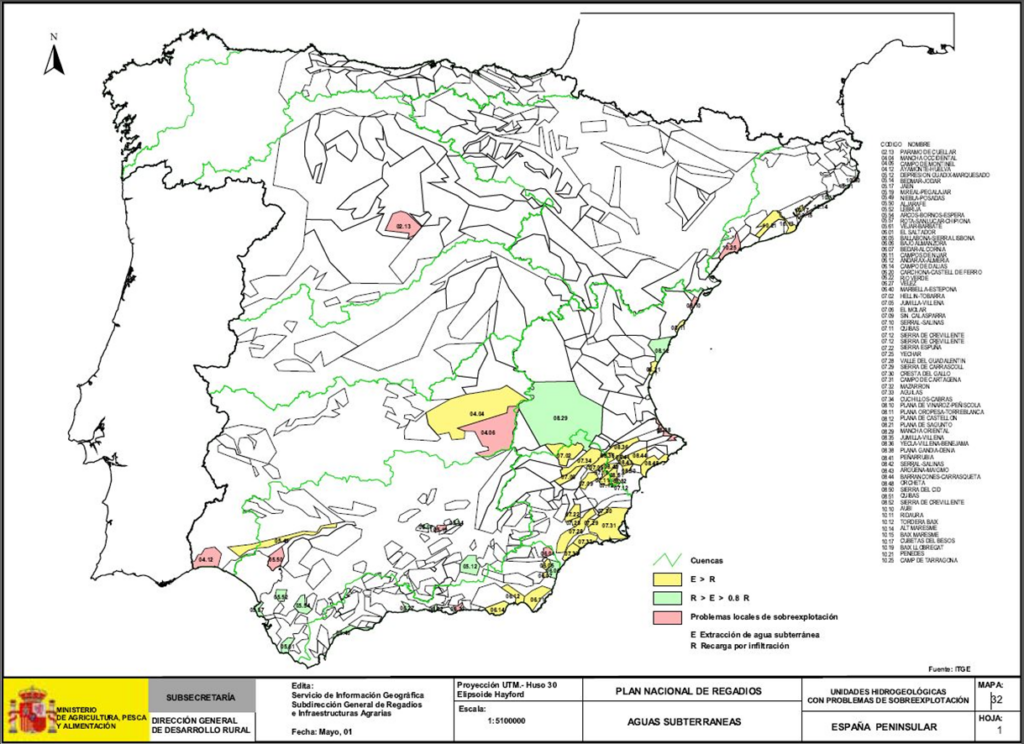

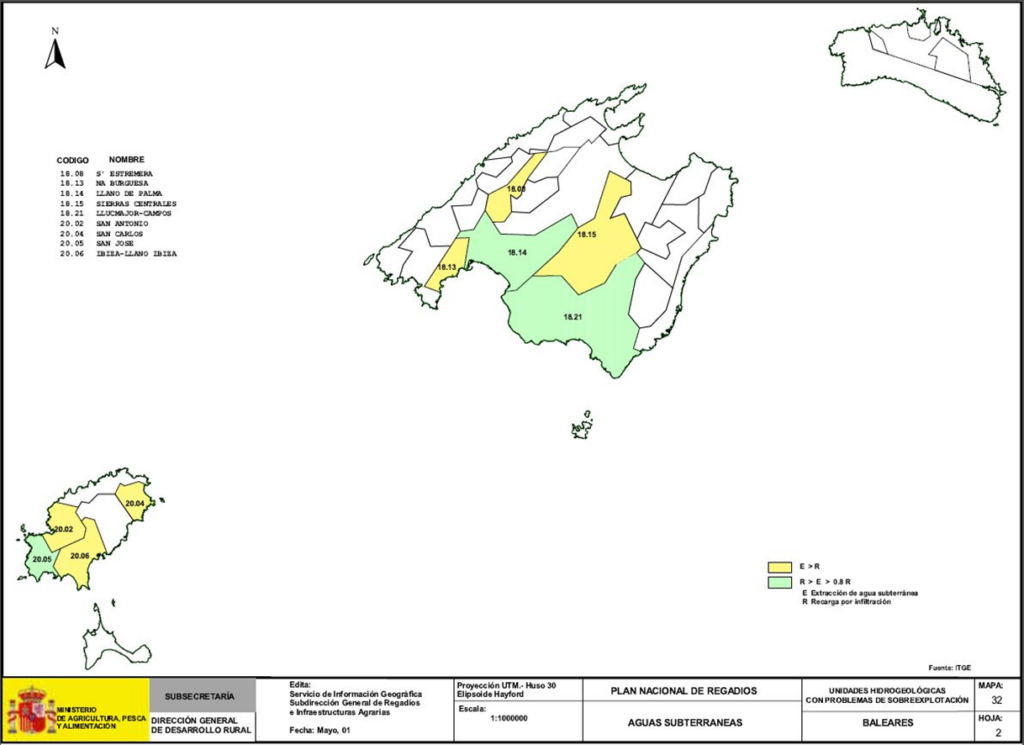

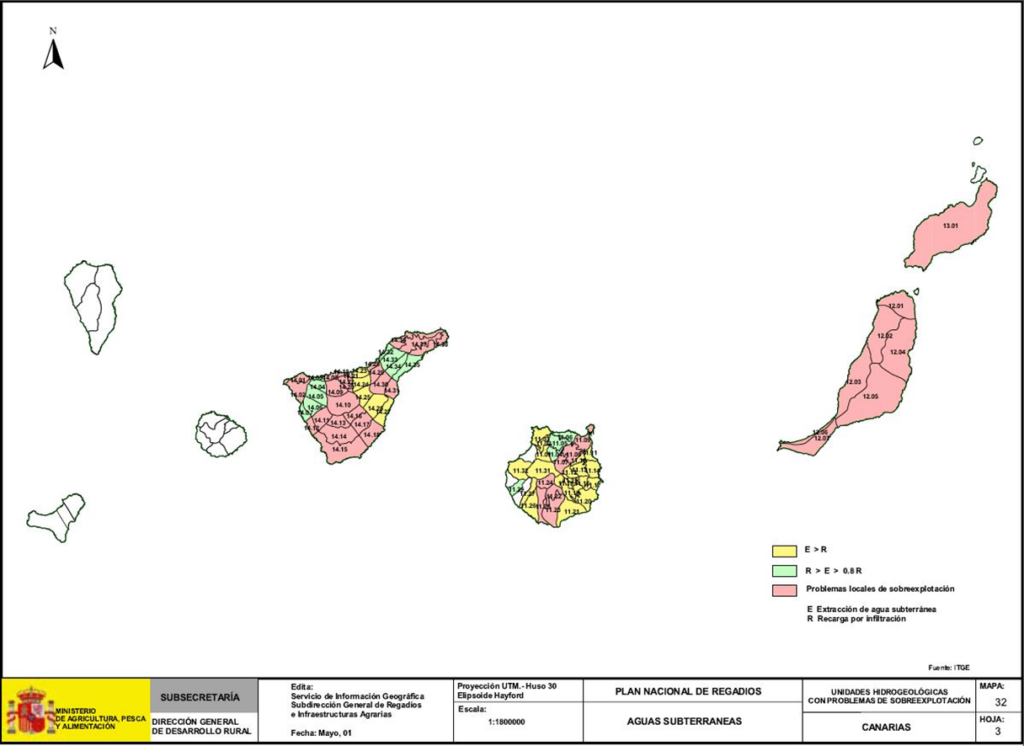

Finally, the importance of irrigation as a water user in Spain cannot be overlooked. Indeed, the irrigation sector is the main user of water in our country. Therefore, any action plan or measure to improve water management in Spain necessarily involves improving the management and use of water in irrigation. When discussing possible measures to improve water use efficiency in Spain, all eyes turn to irrigation. This is essential, because although irrigation contributes only 2.1% of GDP and employs 4.1% of the working population, it consumes 801% of available water resources—resources that are increasingly scarce and degraded, and whose sustainable management is fundamental for environmental conservation. This gives irrigation a central position in water and environmental policies. It will not be possible to increase water use efficiency, recover overexploited aquifers, preserve valuable wetlands, or improve water quality without improving agricultural water use.

1.3 The new institutional framework for water and irrigation

Following the entry into force of Law 29/1985 of August 2, on Water, water policy in Spain has undergone a long evolution, culminating in the recent approval of the National Hydrological Plan Bill in the Congress of Deputies. The approval of Law 29/1985 marked a historic milestone, not only because it repealed a law passed in 1879, but also because it enshrined the public domain status of all waters and granted hydrological planning a fundamental role in the management and administration of water resources and river basins. The planning process completed its first stage with the approval of the River Basin Management Plans through Royal Decree-Law 1664/1998 of July 24.

Although of lower legal standing than the National Hydrological Plan, river basin management plans incorporate elements of fundamental importance for the future of irrigation in Spain. These include the definition and objectives for guaranteeing water allocations to irrigated areas, the regulation of water use during periods of scarcity, projects aimed at increasing the water supply and, therefore, maximizing the potential growth of the irrigable area within the basin, and finally, water conservation objectives achievable through modernization and rehabilitation projects in irrigated areas. The approval of the National Hydrological Plan Law concludes the process initiated on January 1, 1986, with the entry into force of Law 29/1985, while also establishing the growth of irrigable areas for the next twenty years in those basins that, in accordance with the Law, are eligible to do so. Thus, although with different timeframes, irrigation planning is subordinate to the works and projects included in the National Hydrological Plan Law and linked to the provisions of said Plan.

The amendment to Law 29/1985 on Water, through the approval of Law 13/1999 of December 13, by raising the standards for the regulation and preservation of public water resources, poses new challenges for agricultural water use. The mandatory installation of water consumption meters, the possibility of increasing or decreasing fees and tariffs based on the flow rates consumed by irrigators, and the contracts for the transfer of water rights are essential elements for rationalizing agricultural use, but they are difficult to implement without modernizing obsolete, deteriorated, or structurally unsound irrigation systems.

The accelerated pace of legal modifications culminated in the approval at the end of 2000 of the Water Framework Directive 2000, after which a period began, concluding in 2012, for Member States to demonstrate their improved compliance. The desire and need to rationalize agricultural water use is implicitly or explicitly present in all current planning elements and legal texts. However, fulfilling this need is severely limited, if not impossible, in older irrigation systems or those undergoing structural and social deterioration and aging. It is inconceivable that the effort and awareness of irrigators in older communities or irrigation districts would be sufficient to undertake modernization projects, without which the changes to our legal framework cannot be implemented. This National Irrigation Plan is inspired by the growing need to rationalize the use of water in all Spanish irrigable areas, new or old, harmonizing the objectives of water policy with the improvement in the living conditions of irrigators, rural development and the increase of their competitiveness in agricultural markets.

1.4 Need for general irrigation planning

Irrigation planning in Spain is a mandatory task, due to all the factors indicated below, without the order in which they are presented implying any order of priority.

The first factor is the need to incorporate into irrigation policy the profound institutional, social, and economic changes that have occurred in the last fifteen years and that are influencing the evolution of irrigation in Spain. Among these changes, the following stand out: the transfer of functions and services for agricultural reform and development from the central government to the regional governments, including those related to irrigation; Spain's accession to the EU, with full participation in its Regulations and Directives, within which its own policies must be developed; the strategic importance that the current Water Law confers on hydrological planning; and the consideration of water as an economic good (a scarce resource), which means that agriculture must compete with other water uses, among which environmental concerns have strongly influenced social demands. And finally, the growing trend towards globalization and the progressive opening of agricultural markets, which requires improving the productive efficiency and competitiveness of the agri-food chain, starting with the first link, which are the agricultural holdings, in whose competitiveness irrigation is a decisive factor.

The second factor is the need to frame the development of irrigation within the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and the sustainable development enshrined in Article 2 of the Treaty of Amsterdam. The current CAP maintains a significant level of support for the main productive sectors, but limits, in each of them, the national, regional, or individual amount of production, land area, or livestock that can receive the corresponding support through price or direct aid. Only fruits and vegetables, wine, and industrial livestock farming (pigs and poultry) are excluded from this approach; these sectors do not receive direct aid or price guarantees. However, in the case of wine and certain fruits, there are specific prohibitions on new plantings and/or grubbing-up aid, which limits production expansion, at least for some varieties. Approximately 801% of dryland and 651% of irrigated land are subject to some form of supply limitation (quotas, allocations, premium entitlements, base areas, base livestock numbers, or maximum guaranteed quantities). These production limitations necessitate national policies for coordination and management to prevent potential overshoots and the resulting penalties.

In a single market, the uncontrolled increase in irrigated agricultural production in some regions ultimately has a negative impact on all others due to falling agricultural prices or widespread penalties in aid for overproduction. This interrelationship between regional agricultural production requires public authorities to organize and coordinate their actions to prevent imbalances in agricultural productivity, particularly those that could arise from the transformation and disorderly growth of irrigated land. Therefore, a national framework for irrigation action is necessary, serving the sustainable development of rural areas, a coherent policy for regulating production and markets, and the efficient management of a scarce resource such as water.

The third factor is the legal mandate for irrigation planning in Spain. This legal mandate stems from the 1985 Water Law and, more recently, from Royal Decree 1664/98, which approved the River Basin Management Plans. Indeed, the Water Law establishes that the River Basin Management Plans and the National Hydrological Plan must take into account the various sectoral plans and must include the basic regulations on improvements and transformations in irrigation that ensure the best use of all available water resources and land. The Royal Decree that approved the River Basin Management Plans in 1998 is even more explicit, establishing that the construction of hydraulic infrastructure promoted by the General State Administration will be subject to current regulations on environmental impact assessment, budgetary provisions, and the corresponding sectoral plans when their specific regulations so stipulate. In particular, regarding irrigation, the actions and investments of the General State Administration will adhere to the programs, deadlines and forecasts established in the National Irrigation Plan, in force at any given time.

The fourth factor is the parliamentary mandate to carry out irrigation planning in Spain. Indeed, taking into account the importance of irrigated agriculture in hydrological planning, given its status as the main water user, the Congress of Deputies adopted an Agreement in 1994 urging the Government to draw up an Agricultural Irrigation Plan that would include the irrigated areas to be improved, new irrigation systems, transformations for social reasons, water consumption and conservation, the influence of the CAP reform and the GATT agreements on irrigated crops, as well as the necessary profitability studies.

The mission to carry out this parliamentary mandate was not without enormous technical, legal, and political difficulties. Technical difficulties arose from the lack of complete information on the state of existing irrigation systems in Spain; legal difficulties stemmed from the complex network of rules and regulations governing water and irrigation planning in Spain; and political difficulties arose from the distribution of powers regarding irrigation, derived from the State of Autonomies.

The development and approval of a National Irrigation Plan by the Government of Spain is based on Article 149.1.13 of the Spanish Constitution, which establishes as an exclusive competence of the State "The basic principles and coordination of the general planning of economic activity." This power legitimizes the Government of Spain to propose an irrigation plan that, in accordance with constitutional doctrine, is based on consensus, cooperation, and collaboration between the State and the Autonomous Communities in a shared task involving two areas of competence dedicated to the promotion and orderly development of irrigation in Spain.

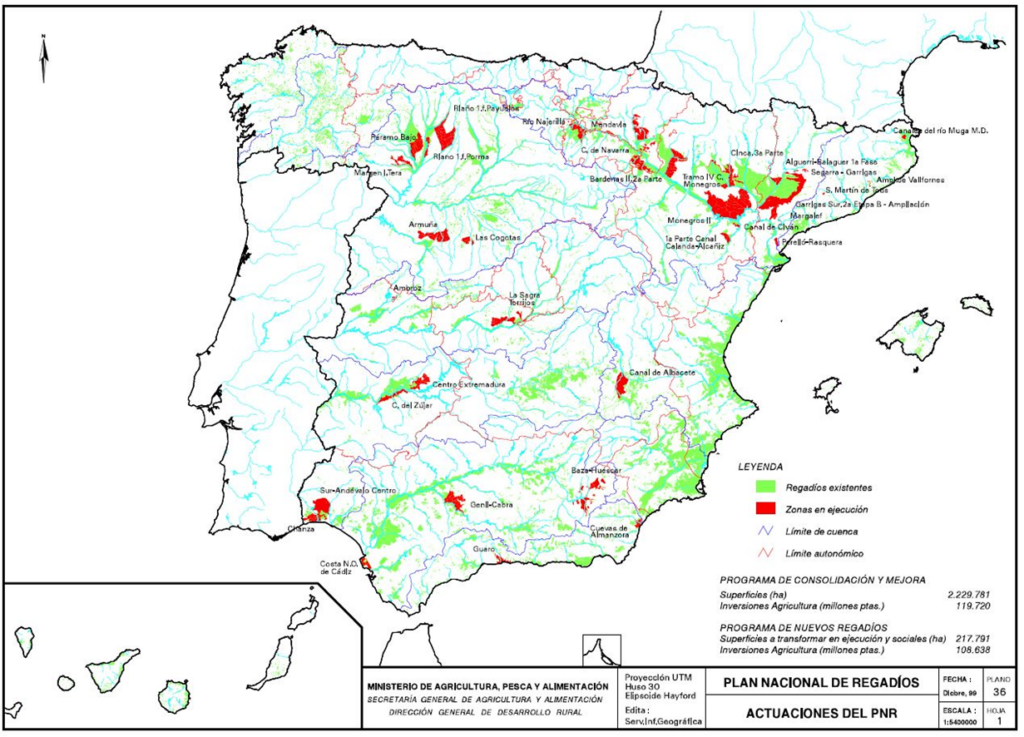

To comply with this parliamentary mandate, the necessary work and studies to develop an Irrigation Plan began in late 1994. Thus, in February 1996, the Council of Ministers approved a Preliminary Draft of the National Irrigation Plan with a timeframe extending to 2005. The completion of baseline studies on the actual state of existing and planned irrigation systems, the need to align irrigation action plans with EU policies, and finally, the joint development process with the Autonomous Communities of Rural Development Programs for the period 2000-2006, all prompted an update of the aforementioned Preliminary Draft, both in terms of its specific objectives and its implementation timeframe. When defining this new time horizon, it was taken into account that obtaining community funding required the new horizon of the PNR to coincide with the programming period of the community structural funds, whose planning covers the period 2000-2006 but whose execution extends until 2008.

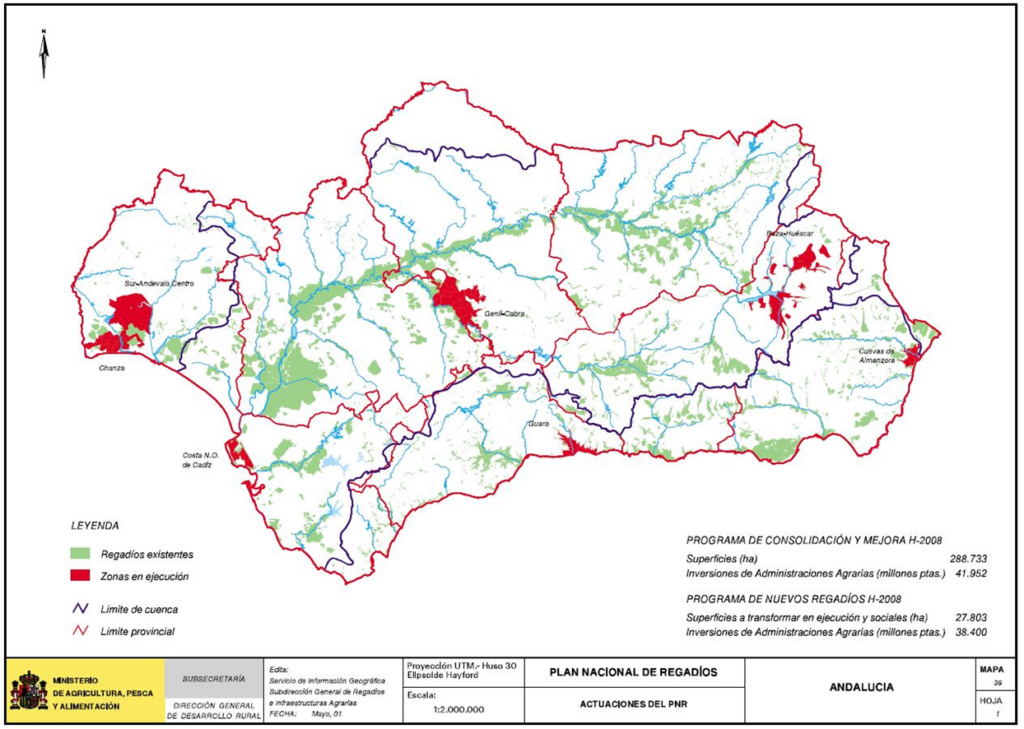

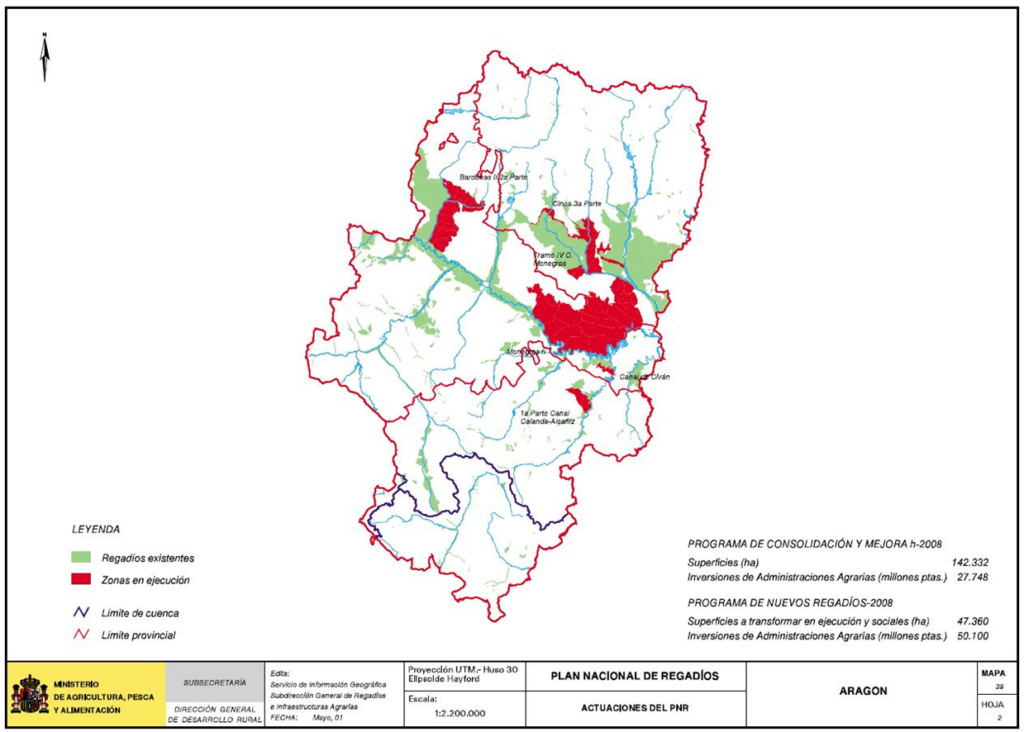

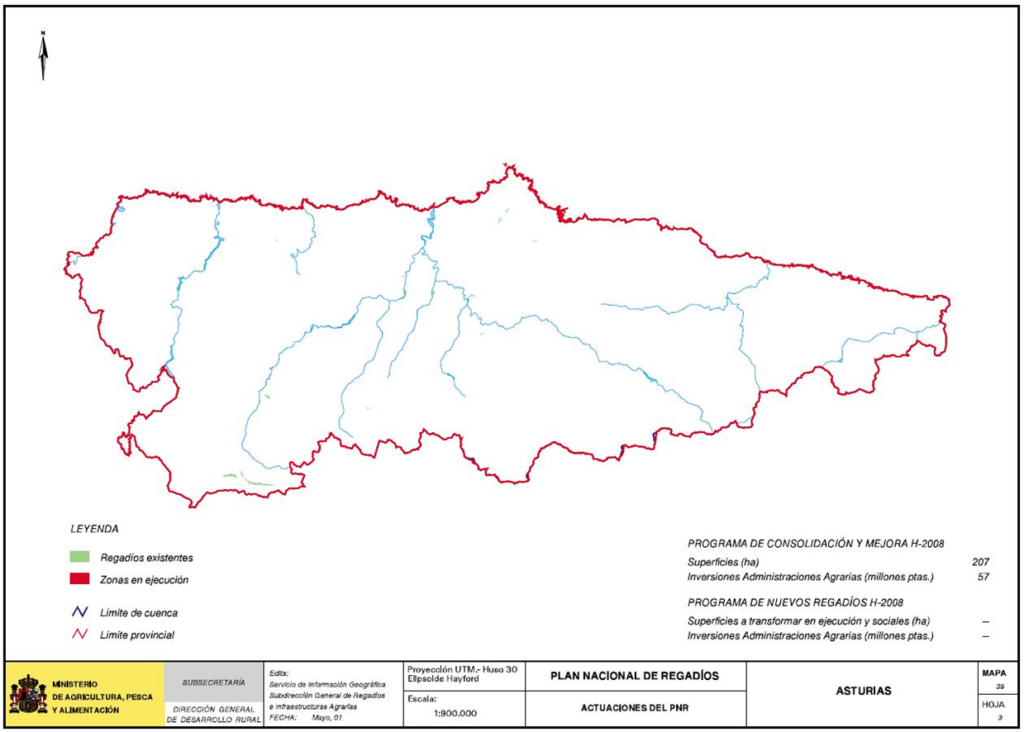

The Rural Development programs (2000-2006) include actions for the Improvement of Agricultural Structures, encompassing water resource management measures in agriculture. Therefore, these programs receive the corresponding European funding to co-finance investments in irrigation, both in Objective 1 regions (Andalusia, Asturias, the Canary Islands, Castile-La Mancha, Castile and León, Extremadura, Galicia, Murcia, and the Valencian Community) and in regions outside Objective 1 (Aragon, the Balearic Islands, Catalonia, La Rioja, Madrid, Navarre, and the Basque Country), as well as in Cantabria as a transitional region.

1.5 General principles and guidelines of a new irrigation policy: national irrigation plan

Irrigation planning must respond to a series of general principles and guidelines that incorporate institutional, economic and social changes, as well as new trends, conceptual approaches and criteria included in the Treaty on European Union and in the Regulations and Directives that directly or indirectly affect the development of irrigation.

The general principles of the National Irrigation Plan Horizon 2008 are sustainability, cohesion, multifunctionality, competitiveness, equity, flexibility, co-responsibility and coordination.

The principle of sustainability applies to new irrigation systems as well as to the improvement and consolidation of existing ones, and encompasses not only environmental sustainability, but also economic and social sustainability. Indeed, an irrigation system will not be sustainable if its production is not profitable or if farmers in irrigated areas abandon rural communities.

The principle of cohesion involves planning a set of social irrigation systems, the purpose of which is to retain population in declining rural areas (rural development) and thus contribute to reducing the differences in income and quality of life between these fragile rural areas and developed rural and urban areas.

Multifunctionality is another general principle that should inform irrigation planning. This involves applying to irrigation this new concept introduced by Agenda 2000 within the definition of the European agricultural model. Therefore, irrigation must fulfill not only the traditional function of food production, to which we must now add the production of safe and high-quality food, but also new functions such as the conservation of natural resources—in this case, water resources—the landscape, and the rural environment, or the retention of population in depressed rural areas to prevent their complete abandonment, which in turn is related to the principle of economic and social cohesion.

Competitiveness is an essential principle that is also related to the principle of sustainability: only competitive irrigation is sustainable. However, it is necessary to delve deeper into the definition of this principle to incorporate certain elements that must be taken into account in the drafting of the National Irrigation Plan (NRP). Today, international competitiveness is greatly distorted by legal, institutional, and political factors. Indeed, the condition of “ceteris paribus”The fundamental principle for comparing the competitiveness of agricultural production in different countries is not being met, as there are significant differences in agricultural, social, and environmental policies, as well as diverse legal regulations and institutional organization between countries, which seriously disrupt analyses of agricultural competitiveness. The World Trade Organization (WTO) attempts to prevent distortions through agricultural policy, but has yet to address those stemming from labor, environmental, social, and other regulations.

Equity, as a general principle of planning, can be interpreted in its territorial sense or from the perspective of users. The former can be considered included within the principle of cohesion, and therefore will not be emphasized. As for the latter, this principle means that a balance must be maintained between user groups so that the benefits for some do not negatively affect others or distort markets, which would be detrimental to farmers and consumers. An illustrative example of the application of this principle is the conversion to irrigated land of large areas where the dominant production orientation is based on crops supported by CAP subsidies subject to limitations.

The principle of flexibility must be incorporated into planning to adapt it, without rigidity, to the changing conditions of the agricultural sector and the extended maturation periods of irrigation systems, within an initial timeframe of 2008 that coincides with the implementation period of the European funds already approved for the 2000-2006 period. This principle is fundamental, given that recent and successive political crises (the collapse of the USSR, the Balkan crisis, uprisings in Asian countries, political instability in Latin American countries, and protests against globalization) and economic crises (Mexico, Russia, Indonesia, Brazil, Japan, and Argentina) occur almost unexpectedly and, above all, at a dizzying pace. No one can predict how global geopolitical balances, economic situations, food security, international regulations and organizations, migration and capital flows, the biotechnological revolution, and other factors will evolve in the future. The only way to protect oneself from so many uncertainties is through flexible planning that is reviewed periodically.

The principle of shared responsibility stems from the fact that powers regarding irrigation are shared between the central government and the regional governments. In practice, this principle translates into the participation of both levels of government in the planning, implementation, and financing of irrigation projects. Logically, the counterpart to shared responsibility is cooperation, meaning that such projects must be planned and agreed upon between the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food and the relevant regional departments of the autonomous communities with jurisdiction over irrigation.

Finally, the principle of institutional coordination must be applied to achieve the essential coherence in the actions of agricultural and water authorities, both national and regional. This will undoubtedly have a multiplier effect on the combined effectiveness of hydrological and irrigation planning. The current coherence between these two planning frameworks will represent a definitive step forward in improving water management in Spain. We must not forget that irrigation planning is a short- and medium-term plan with a time horizon subject to the current situation, but with sufficient flexibility to adapt to the expectations set forth in hydrological planning.

***

In accordance with these general principles, the National Irrigation Plan must be more than just a catalog of public works and actions distributed across the territory according to proportionality criteria based on certain indicators; it must be the expression and reflection of a new irrigation policy that aims to develop rural areas, integrating productive activity with the conservation of natural resources and respect for the environment, in accordance with the following guidelines:

To strengthen the territory, preventing or reducing population loss, abandonment, and aging in rural areas, especially in declining areas where the transformation of small plots of land is of great interest for retaining the working population and creating and maintaining agricultural employment. The economic activity indirectly linked to production in these irrigated areas will also contribute to ensuring the maintenance of basic services and diversifying labor and capital income linked to the regions where they are located.

Improving farmers' living standards by increasing labor productivity and farm income, and promoting the economic growth of their operations. This will help attract young farmers with sufficient training and skills to enhance the competitiveness of irrigated farms and encourage more efficient water use.

To organize agricultural production and markets, consolidating a competitive, sustainable, and diversified agri-food system, and adapting it to the CAP, especially its production restrictions and limitations. The irrigation plan is thus inspired by an integrated vision of agri-food final goods production, according to which improvements in standardization and quality, and greater alignment with end markets, not only result in greater profitability for farms, but also allow processing and distribution industries to compete more effectively in the European single market.

Improving irrigation water distribution and application infrastructure aims to rationalize water resource use, reduce agricultural pollution of surface and groundwater, and promote the modernization of irrigation systems by incorporating technological innovations that allow for less water-intensive irrigation techniques. The irrigation plan views water management as a continuous process, traversing a long path from the reservoir or aquifer to the plant. Along this path, numerous opportunities exist to improve the productivity of the resources used, but its complexity necessitates the application of integrated methods. Without these methods, it is impossible to identify the most effective combination of actions for each circumstance and budgetary constraint.

Incorporate environmental criteria into land and water management to prevent degradation, allow the recovery of aquifers and valuable natural spaces (wetlands), protect biodiversity and landscapes, and reduce desertification processes.

***

These principles and general guidelines lead to new orientations in irrigation policy which, in a balanced way, are intended to be promoted with this National Irrigation Plan in terms of priorities and co-responsibility for the actions to be developed.

First, the improvement, modernization, and consolidation of existing irrigation systems, especially those aimed at rationalizing water use, are considered priorities, and in the medium term, the initiation of large-scale transformations in new irrigated areas is excluded. The only new transformations contemplated in these guidelines are small-scale irrigation projects in disadvantaged or relatively underdeveloped rural areas, with the aim of creating jobs, retaining population, and diversifying production, thus contributing to the socioeconomic organization and balance of the territory. In areas where transformation plans are currently underway, these plans will continue on a moderate scale, but with selective criteria based on profitability, optimization of existing investments, and productive, social, and environmental sustainability.

Secondly, the implementation of the actions will be shared and coordinated among the various public administrations with jurisdiction over irrigation. This coordination is ensured in this sectoral planning, as the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (MAPA) and the Autonomous Communities agree on territorial objectives, coordinate actions, and jointly establish the implementation instruments, among which the specific collaboration agreements stand out.

Finally, the new guidelines reinforce the co-responsibility of irrigators in the actions that affect them, since the current support mechanisms are expanded with new possibilities to expedite and finance projects for the improvement, modernization and consolidation of irrigated areas.

These guidelines introduce a reasonable balance between the productive, social and territorial functions of irrigated agriculture in a way that is compatible with the provision of environmental public goods.

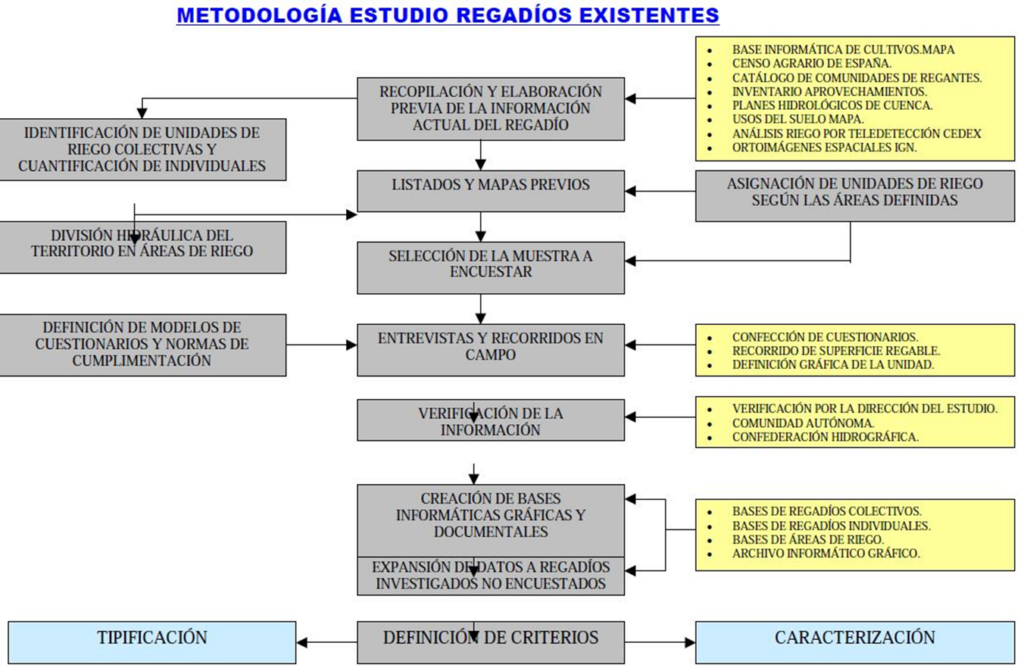

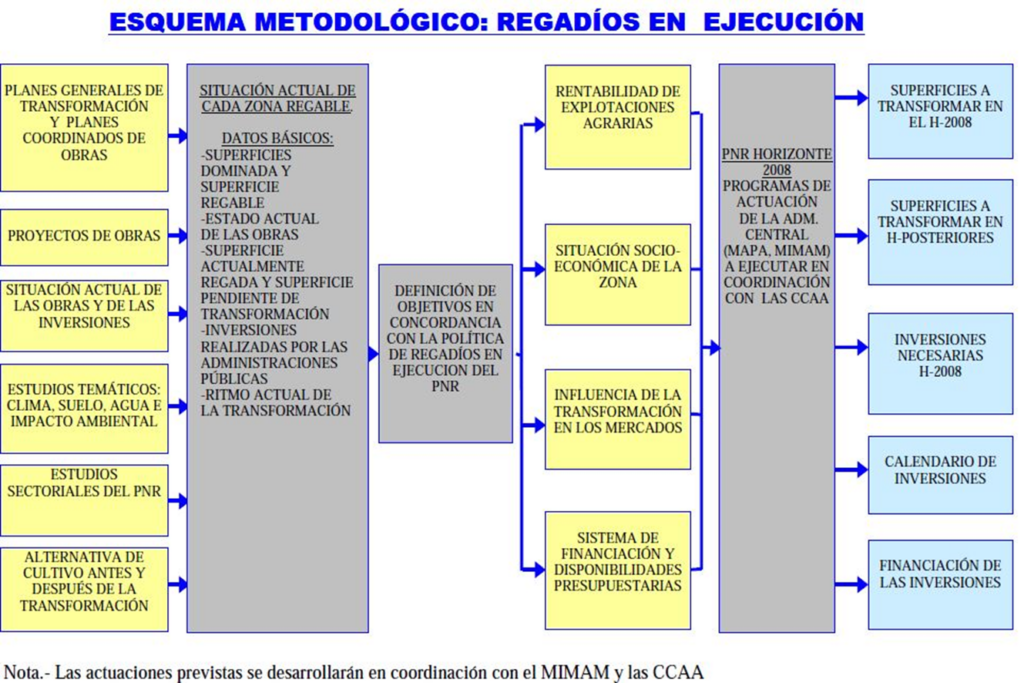

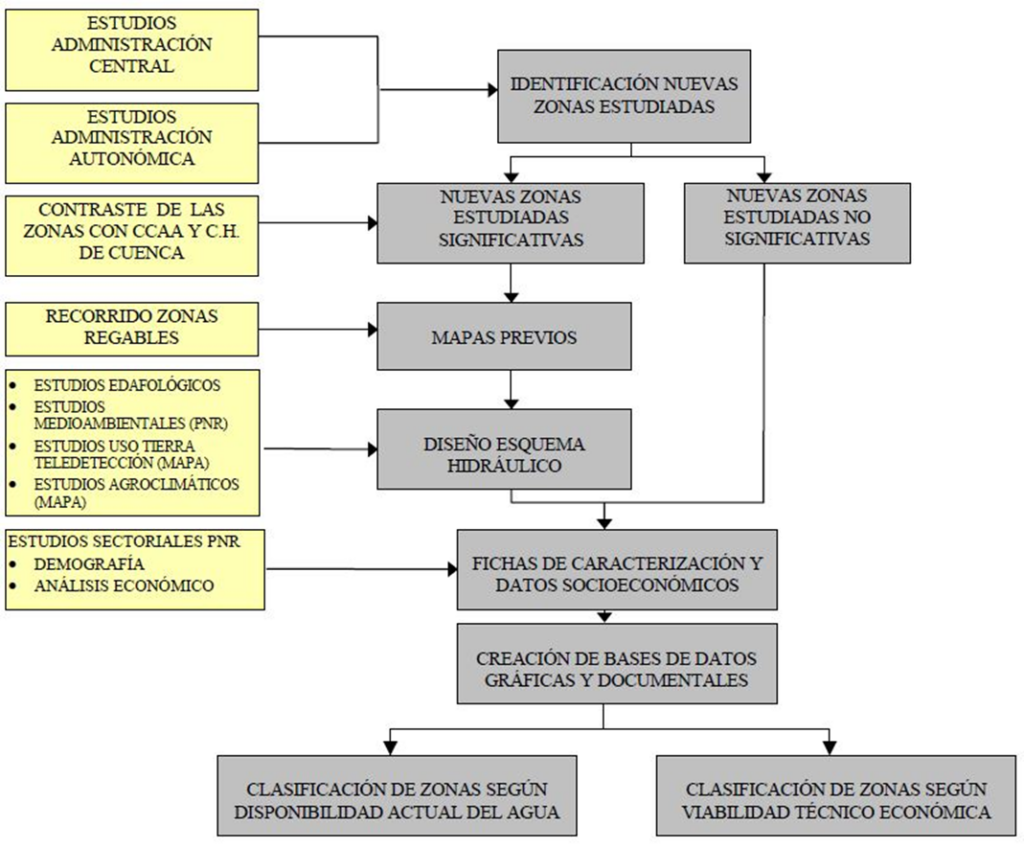

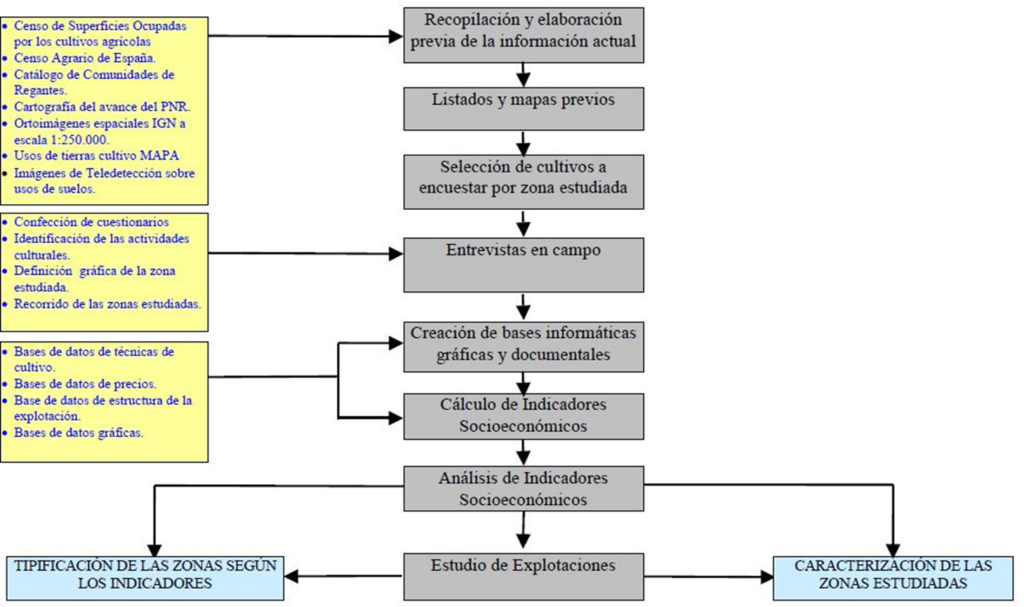

2 Development of the PNR: methodological synthesis and general structure

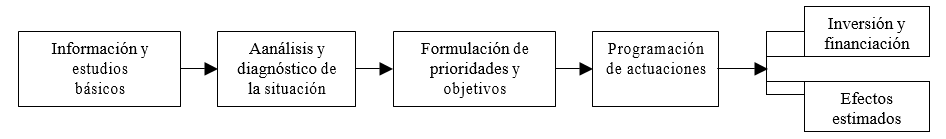

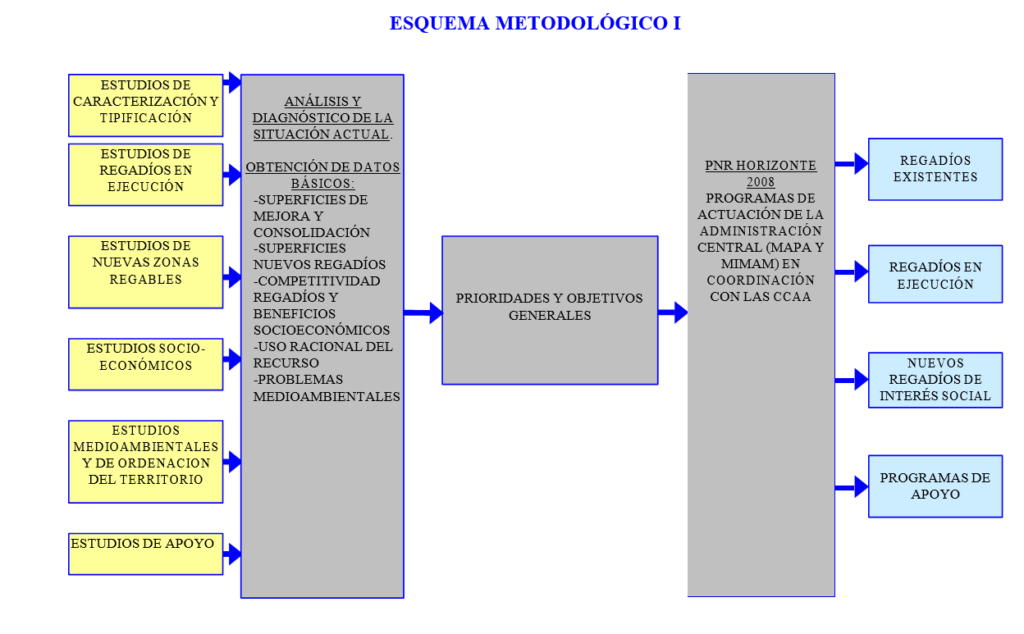

The technical process of developing the National Irrigation Plan (PNR) followed a sequence of several interconnected phases, which unfolded within a context of regulatory and institutional changes impacting sectoral irrigation planning. The development sequence, corresponding to the various chapters that structure the Plan, was as follows:

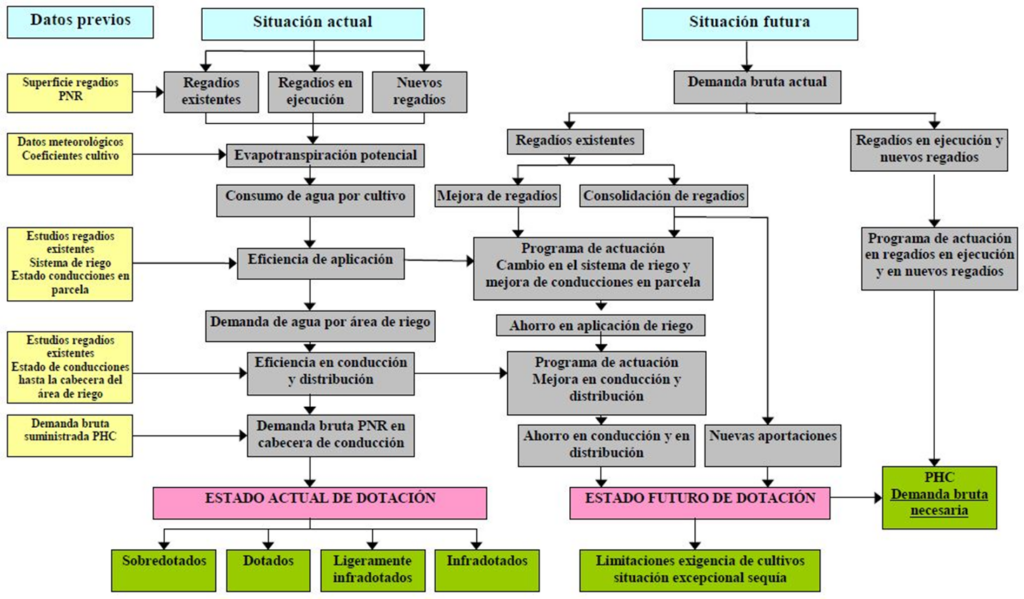

This sequence is outlined in a more detailed way in the two attached diagrams.

- Basic information and studies

The planning and programming of actions must be based on prior, multidisciplinary and as broad information as necessary, regarding its physical and territorial base and all the complex relationships and cross-effects between economic development, regional balance and productive, social and environmental sustainability.

Therefore, the collection, updating and processing of information and statistical data obtained from different sources on the physical and human environment, different aspects of the agricultural economy and environmental issues was carried out, with which graphic and documentary databases have been created, whose management and exploitation is carried out through the Geographic Information System (GIS) of the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food.

Based on all this information and all the studies carried out, Chapter 3 summarizes the most characteristic aspects of agriculture in relation to irrigation. The first sections of the chapter provide data on the natural conditions in which agricultural activity takes place (section 3.1) and describe the demographic context of rural areas and the influence of irrigation on demographic trends and rural employment (section 3.2).

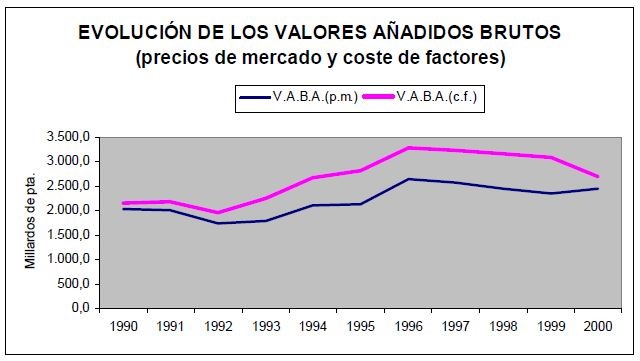

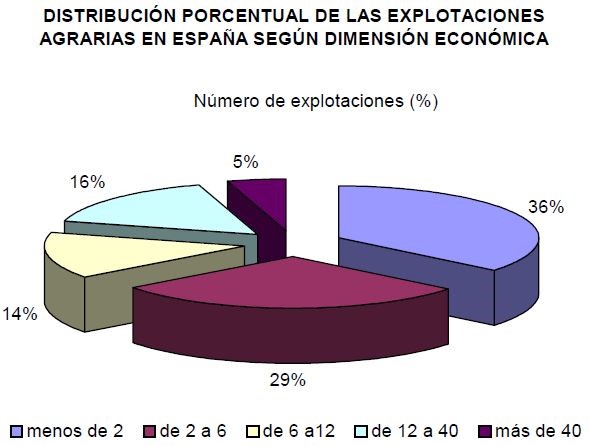

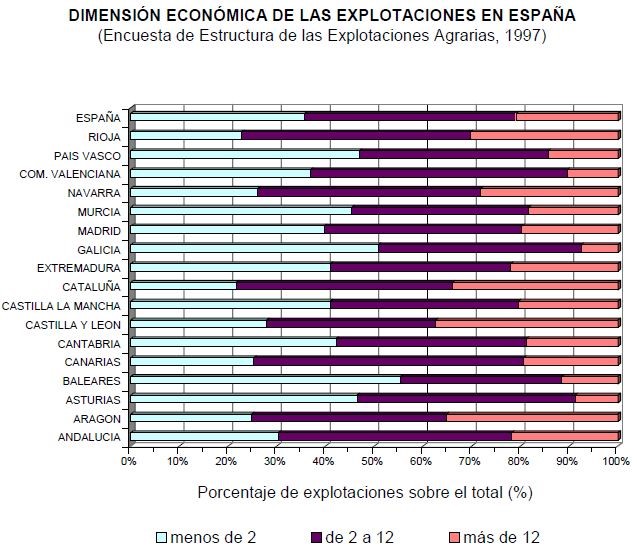

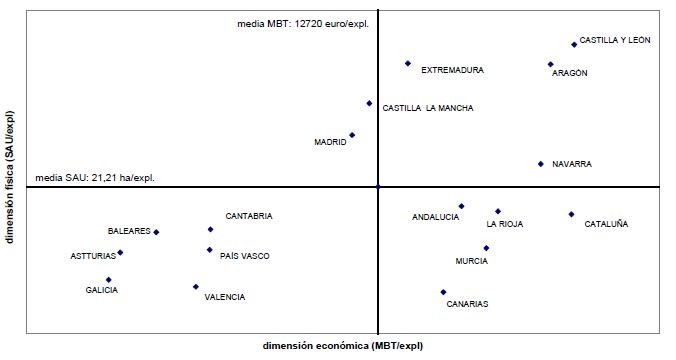

The following sections of the chapter attempt to situate agriculture within its macroeconomic figures, the contribution of agricultural activity to the economy and general employment (section 3.3) and its productive structures of physical and economic dimension (section 3.4).

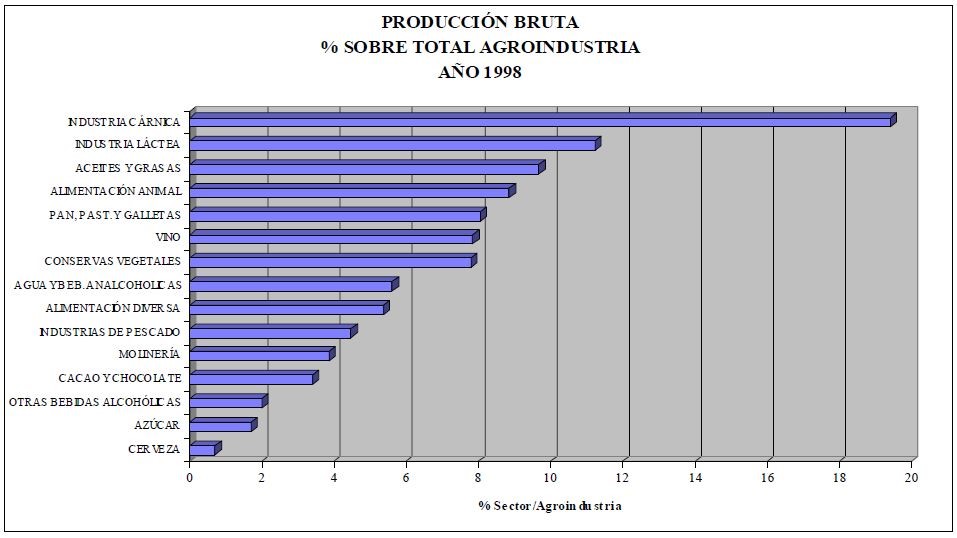

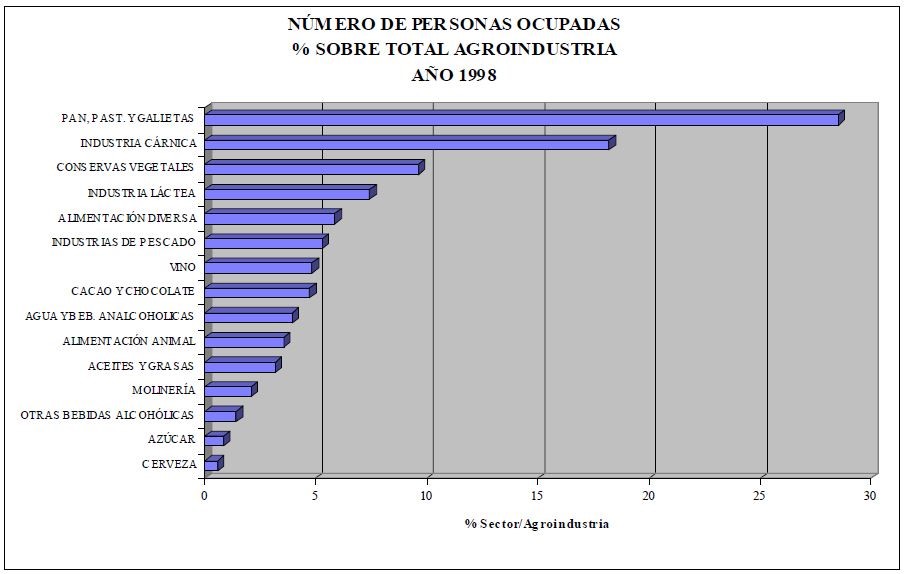

References to the food industry and trade are necessary since they are the destination of a large proportion of many irrigated crops and are crucial for their future (sections 3.6 and 3.7 respectively).

In irrigation planning, especially when new developments are involved, it is essential to study potential production options and market prospects. Section 3.5 describes the different sectors regulated by Common Market Organizations (CMOs), analyzes their situation in Spain, and assesses the production possibilities compatible with increased irrigation. These assessments should be considered estimates subject to revision at any time, given the interdependence between product markets, a characteristic of the agricultural sector (consider, for example, how the BSE crisis offers new opportunities to produce irrigated plant protein for livestock feed that did not exist just a few years ago).

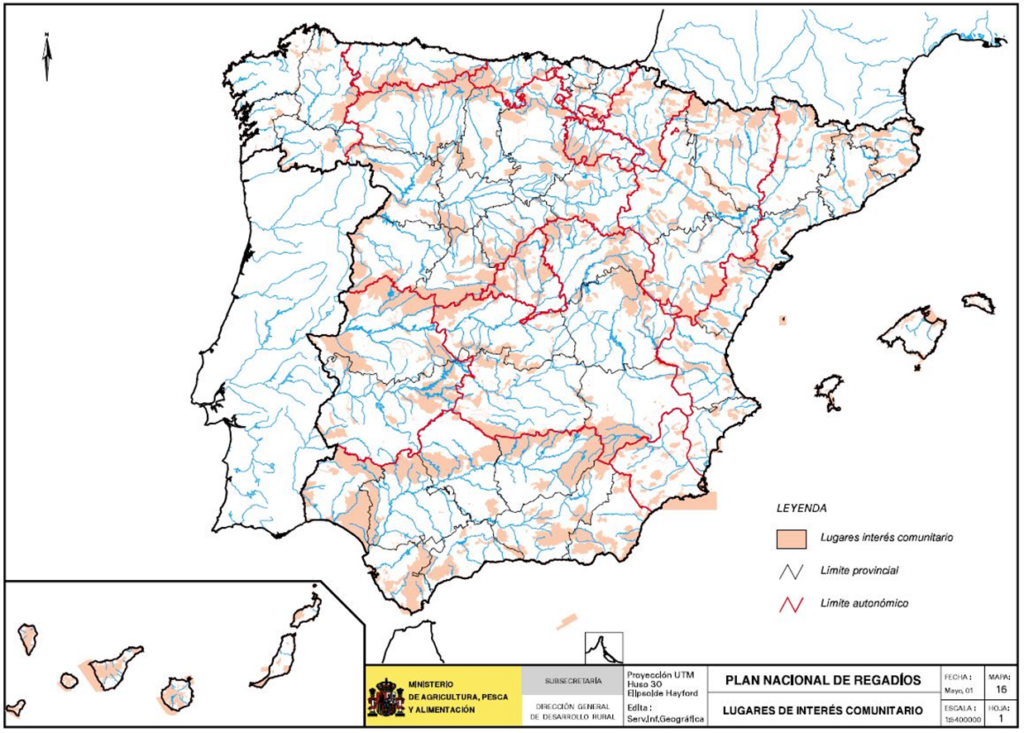

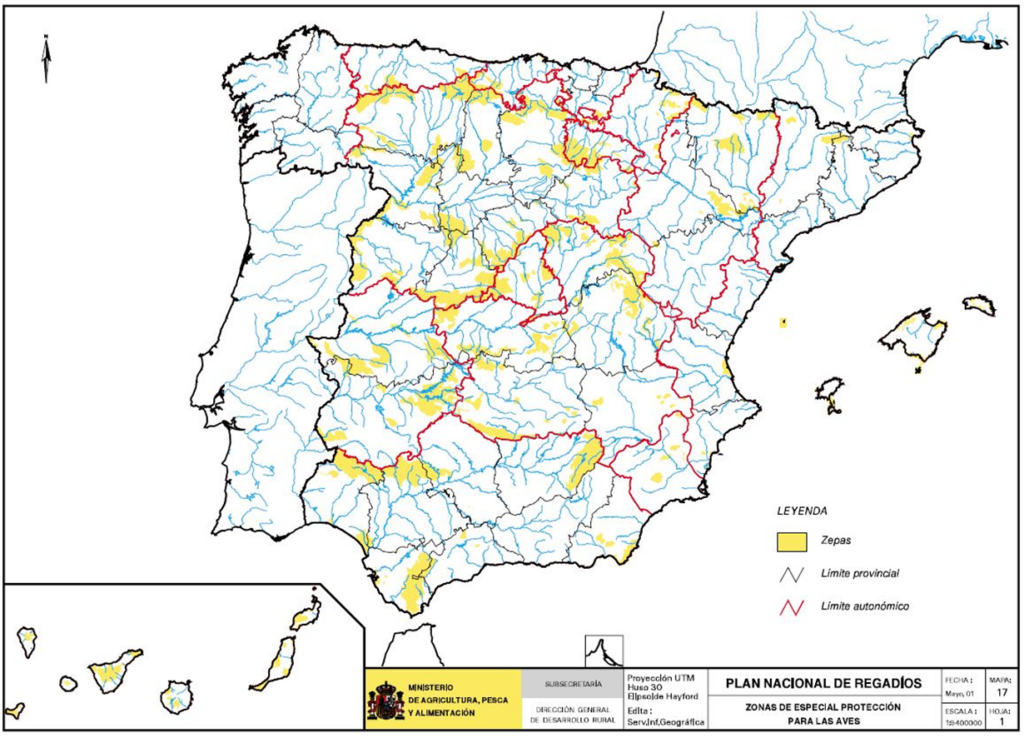

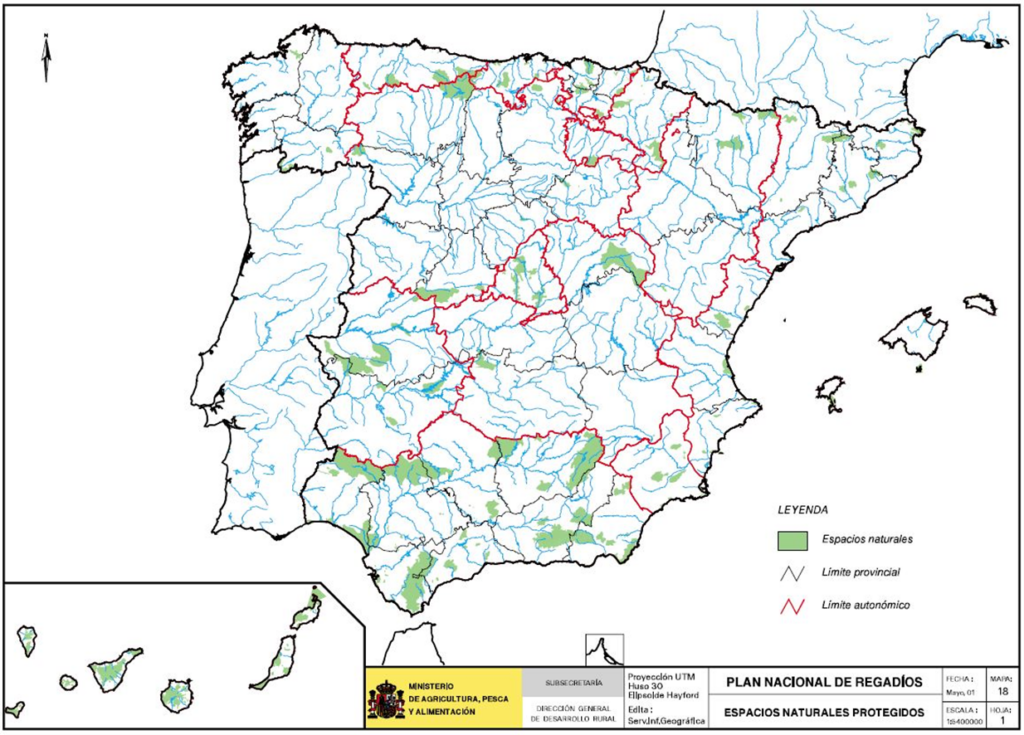

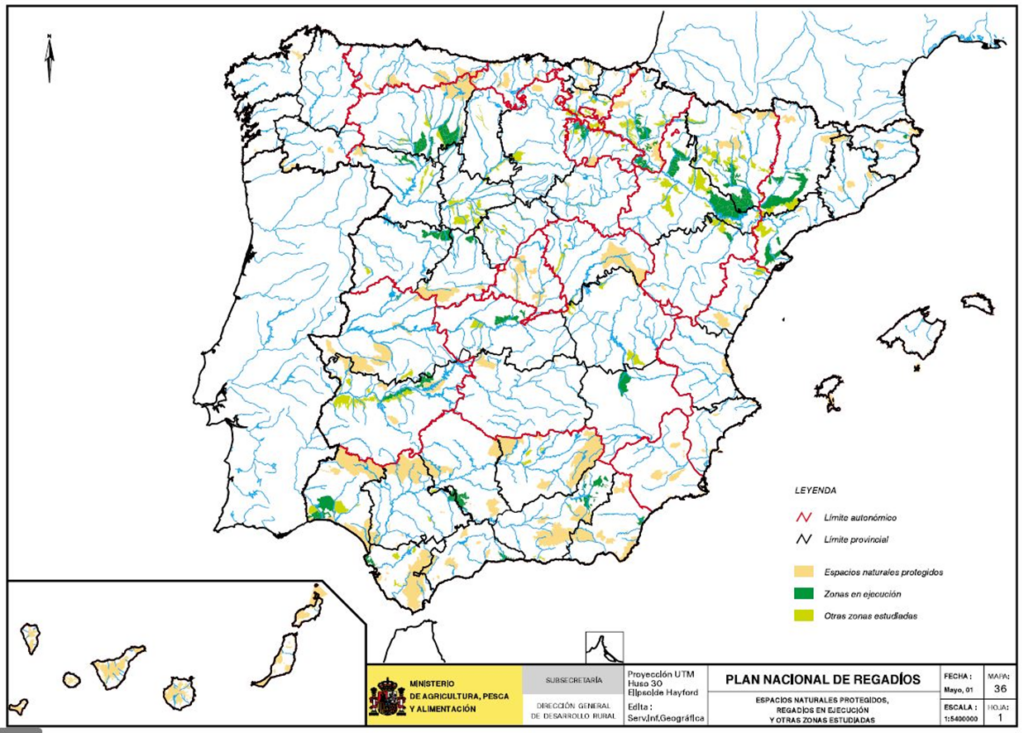

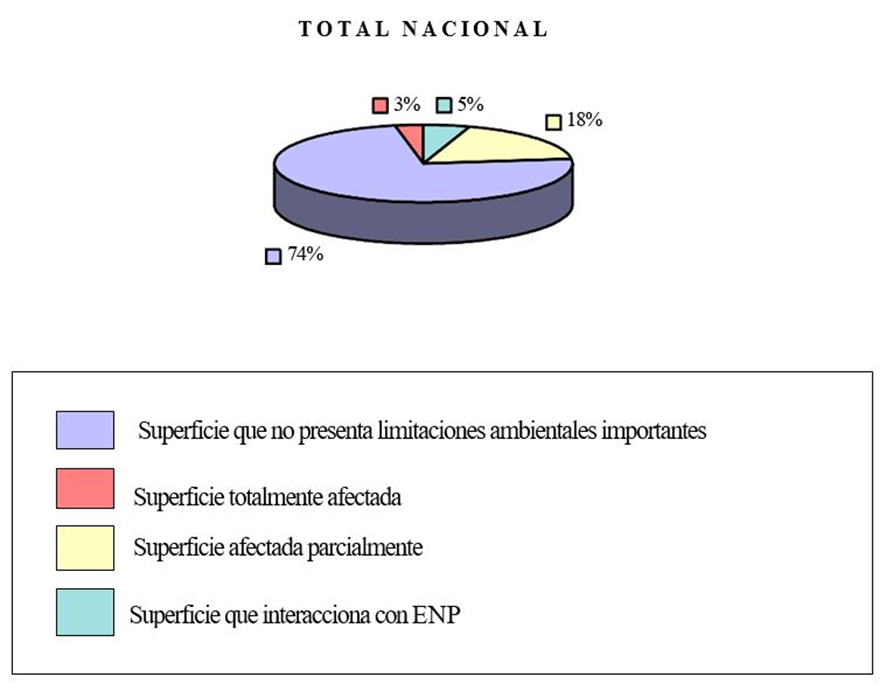

Finally, section 3.8 considers, due to their impact on irrigation, environmental policies and limitations and relates irrigable areas to territories subject to different levels of conservation protection.

- Analysis and diagnosis of the current situation

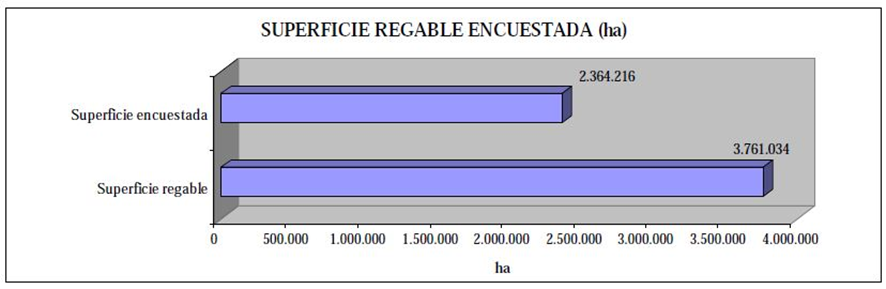

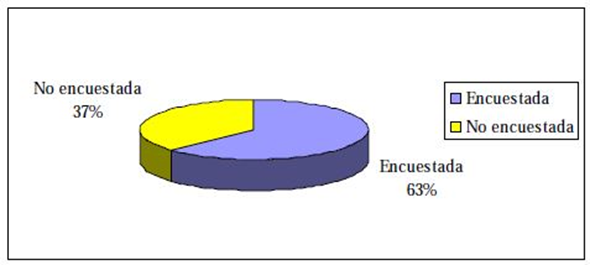

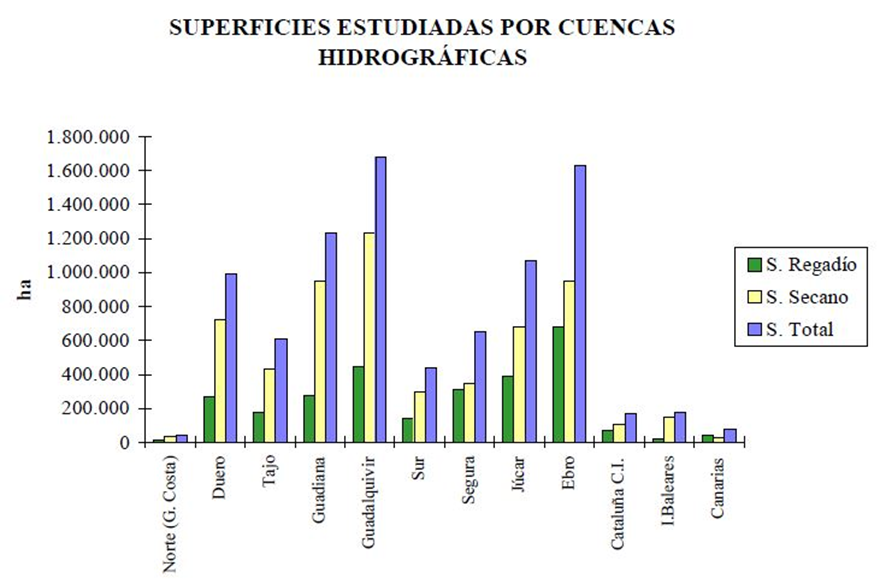

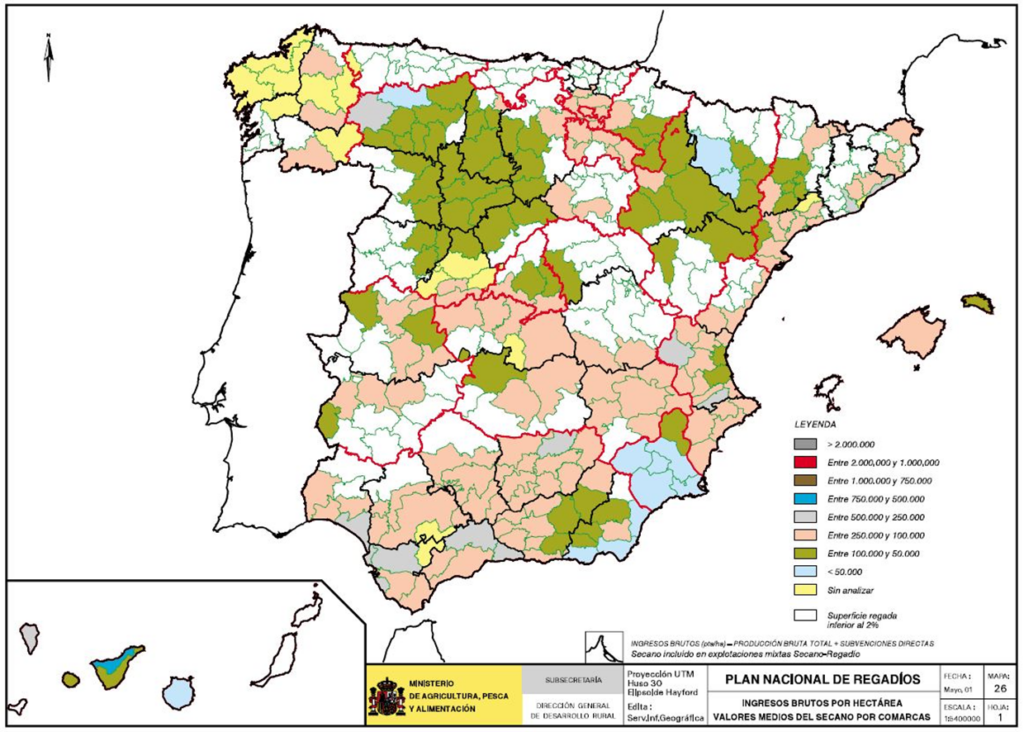

Having established the physical, social, economic, and environmental context in which agriculture operates, it is necessary to analyze, on the one hand, the situation of irrigated lands and diagnose the most relevant problems of those currently in operation or under development, and on the other hand, the potential for initiating new transformations. To this end, studies have been conducted in various areas, among which the following are the most significant:

– Characterization and classification of existing irrigation systems in areas under transformation and other potentially irrigable areas.

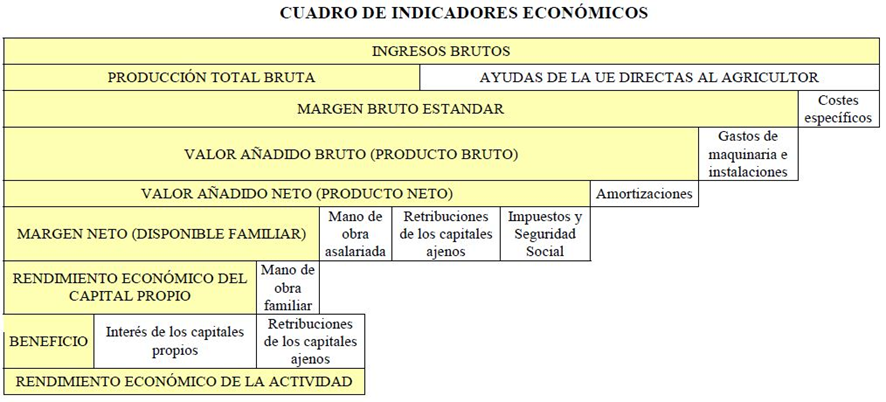

– Economics of agricultural holdings linked to irrigation.

– Water demand and consumption.

– Environmental

– Energy

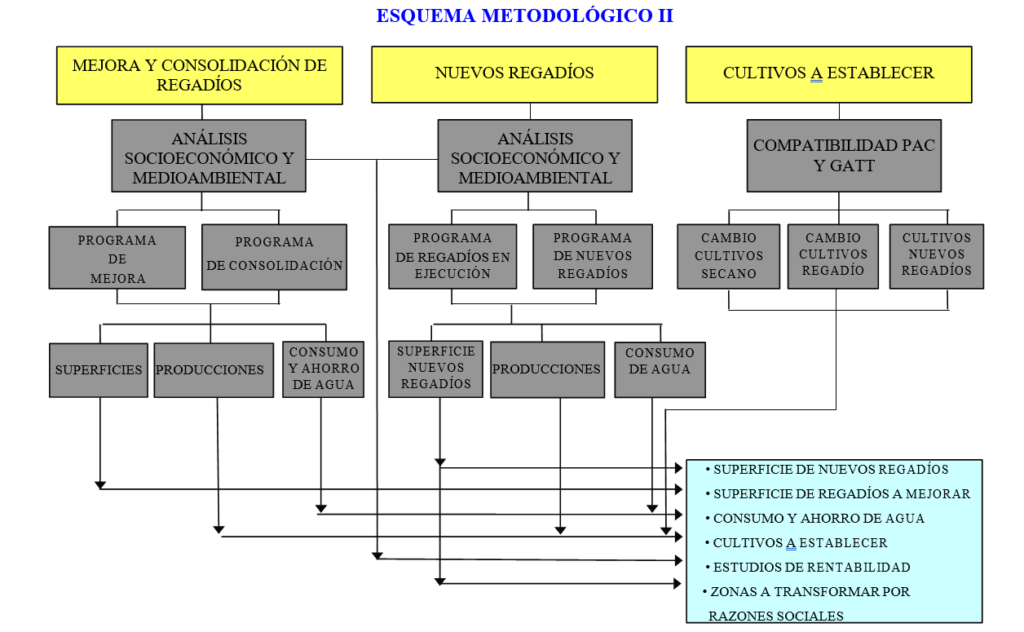

Based on these previous studies, Chapter 4 summarizes the conclusions obtained. Thus, sections 4.2, 4.3, and 4.4 evaluate, respectively, irrigable and irrigated areas from various perspectives (irrigation systems, water source, allocations, infrastructure status, etc.), irrigable areas under development (administrative status, area characteristics, irrigation systems, soil, current production of the works, etc.), and new potentially irrigable areas.

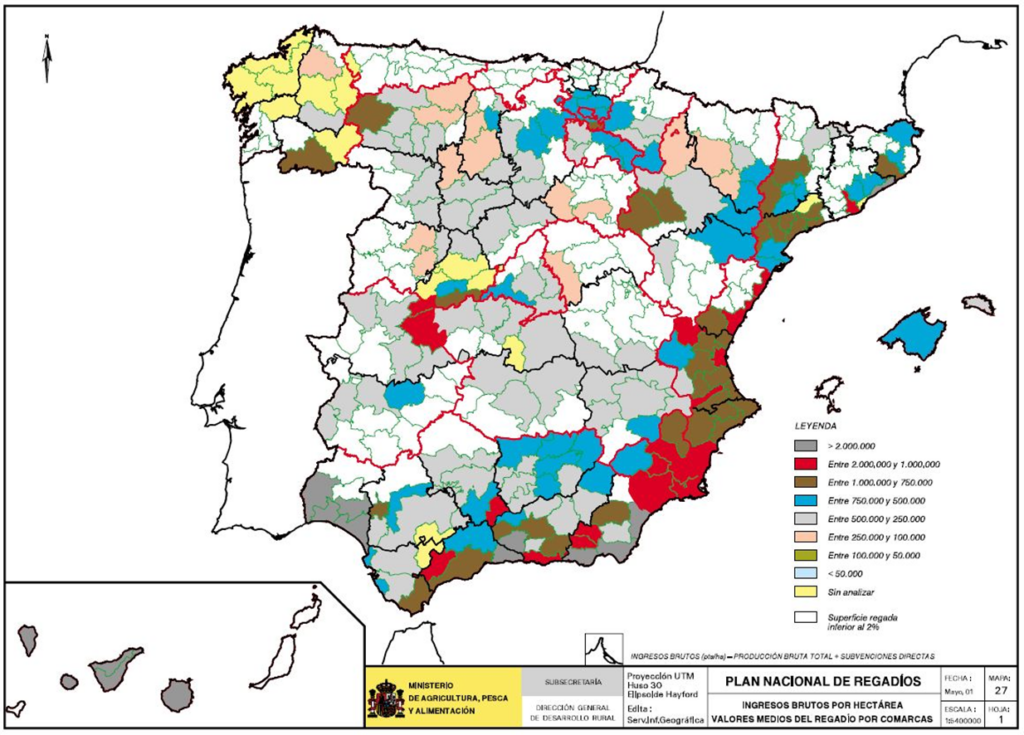

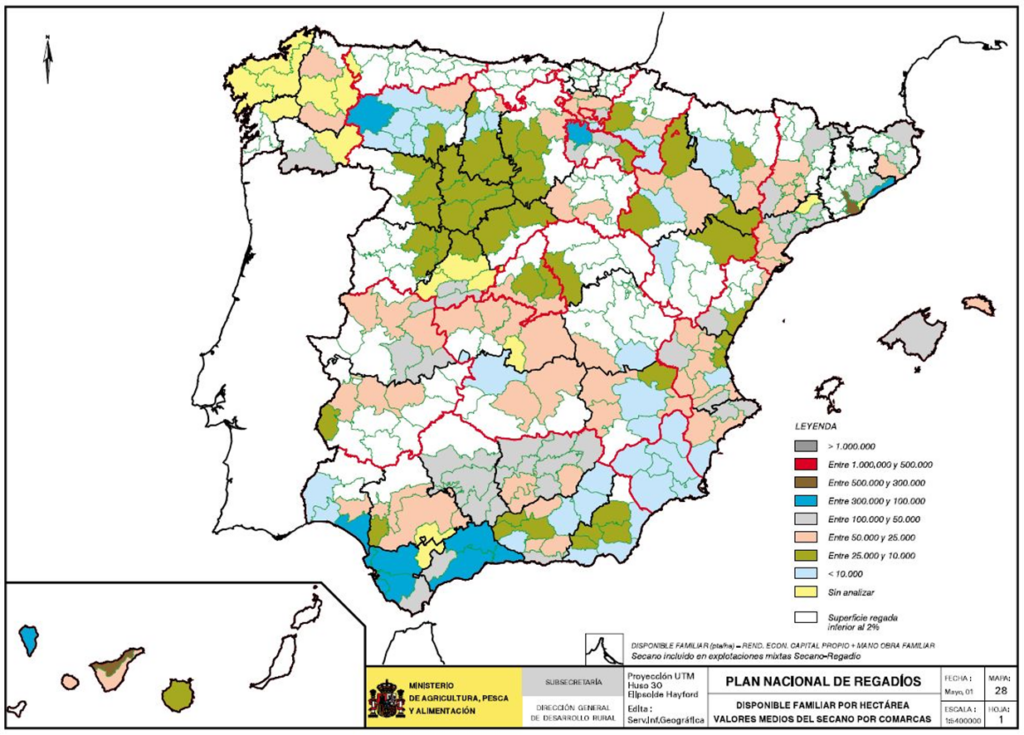

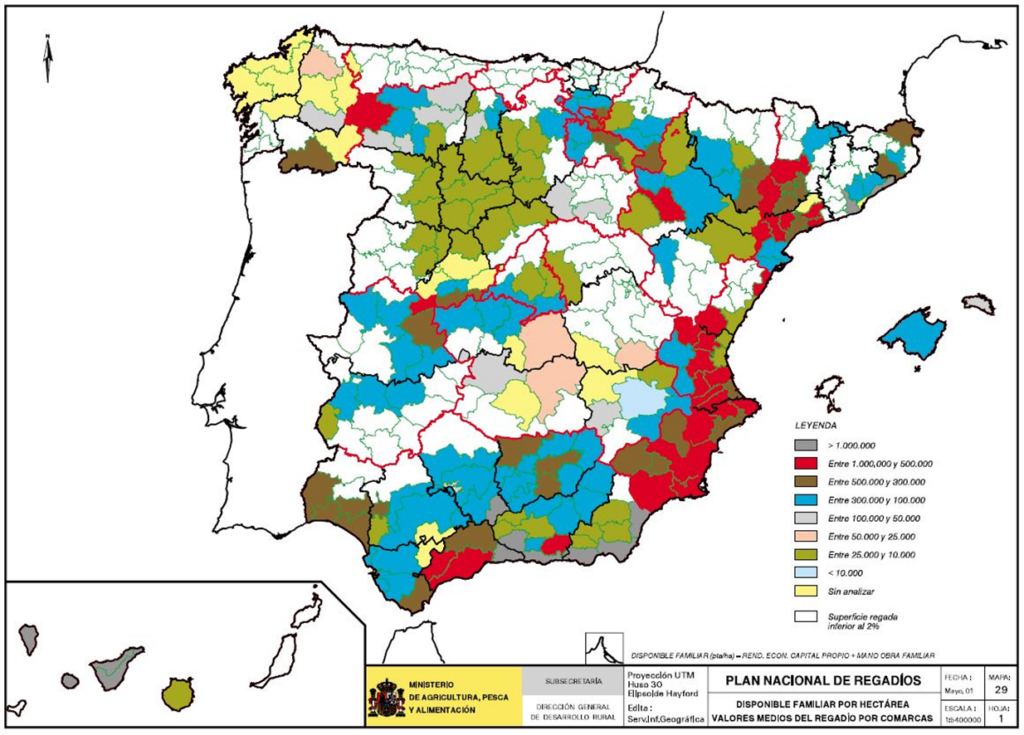

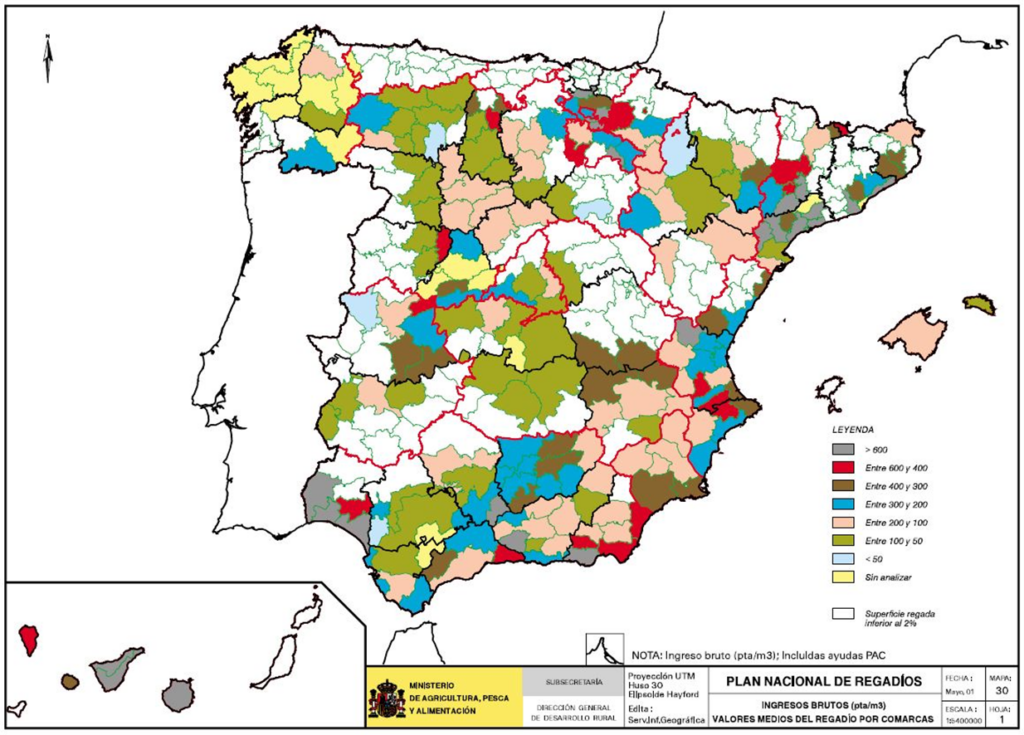

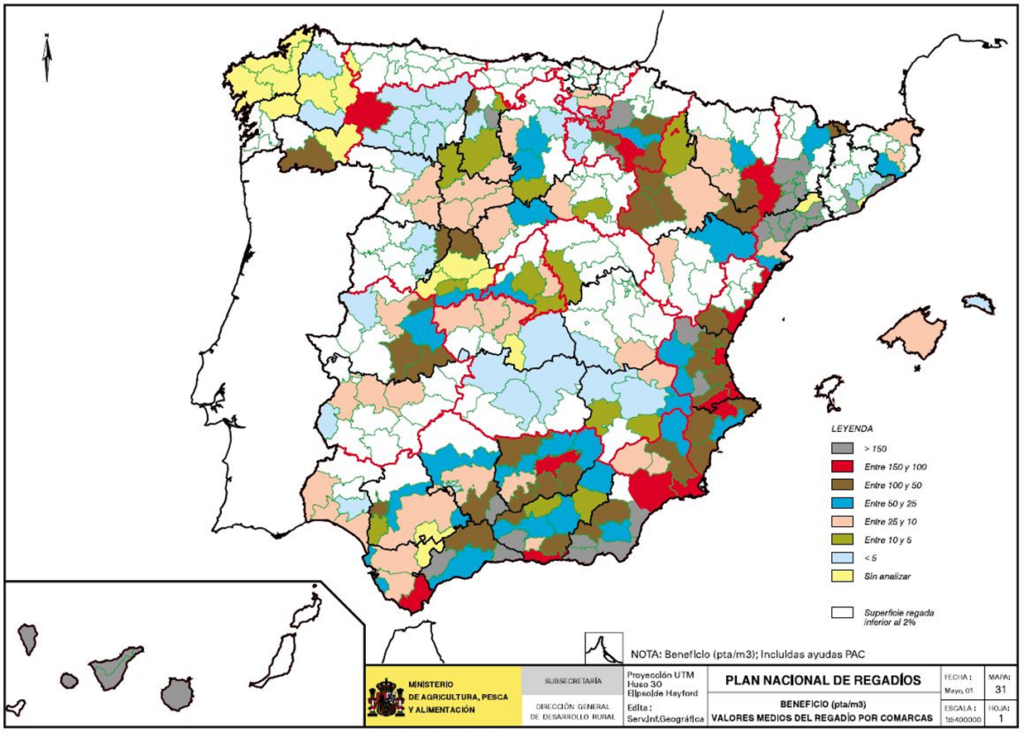

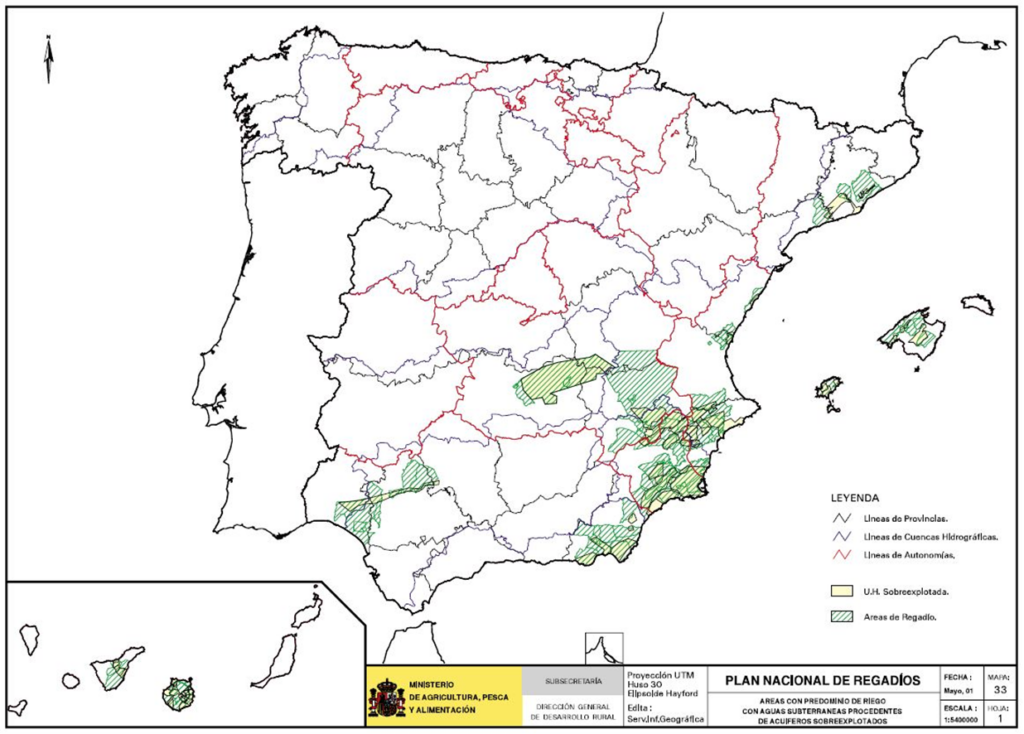

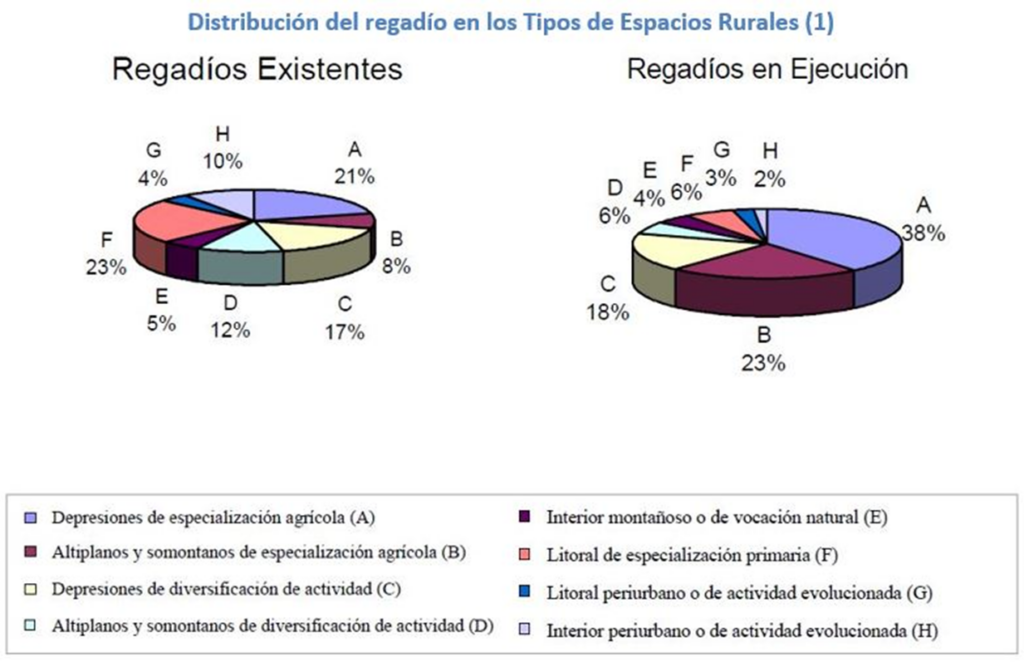

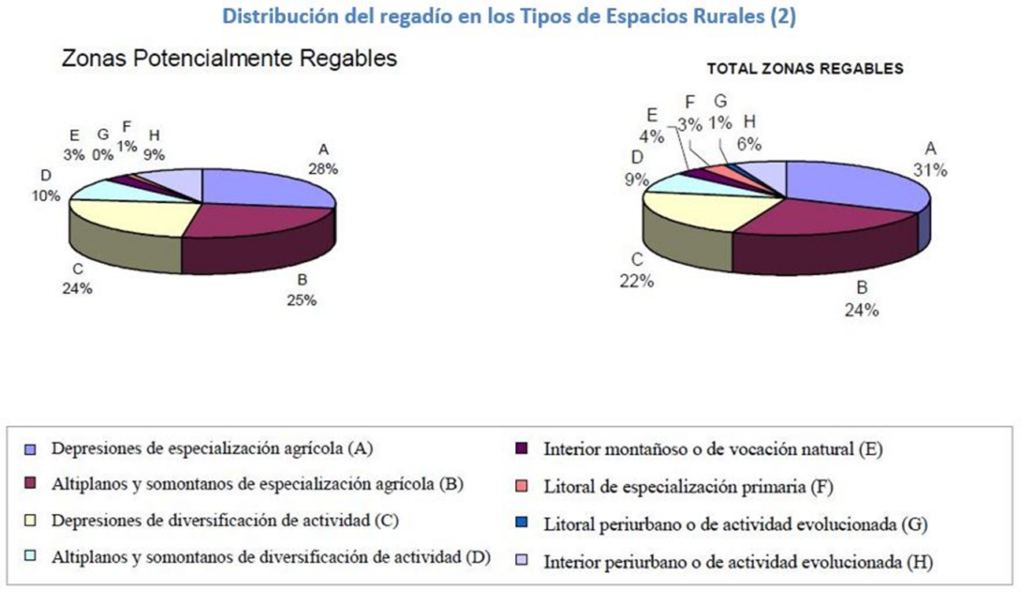

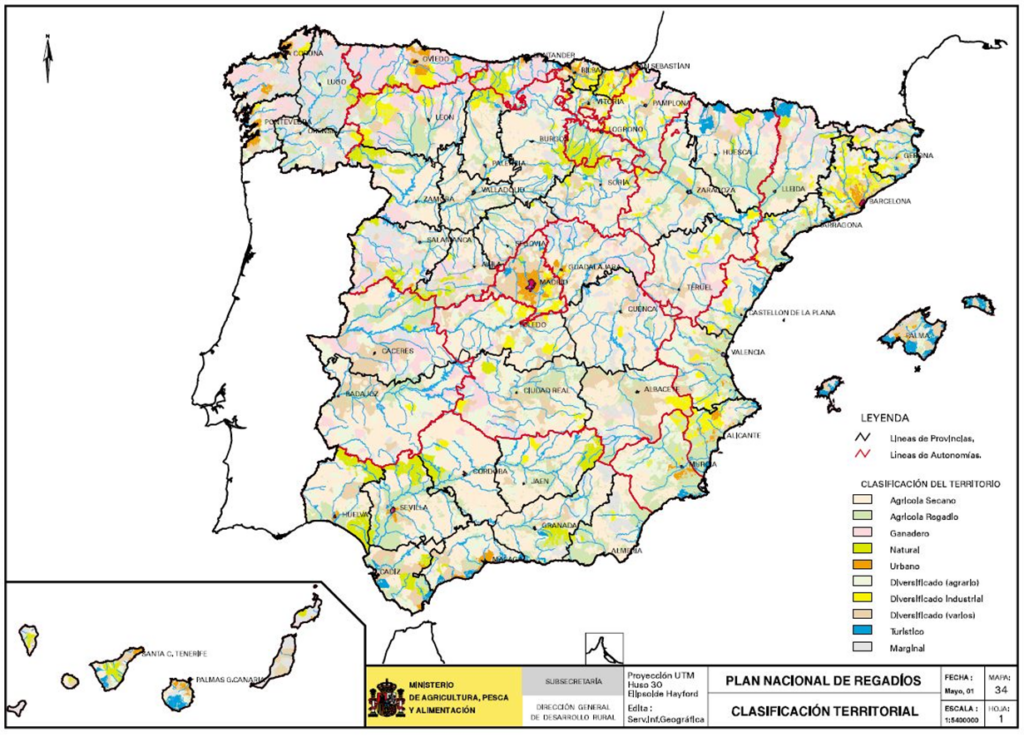

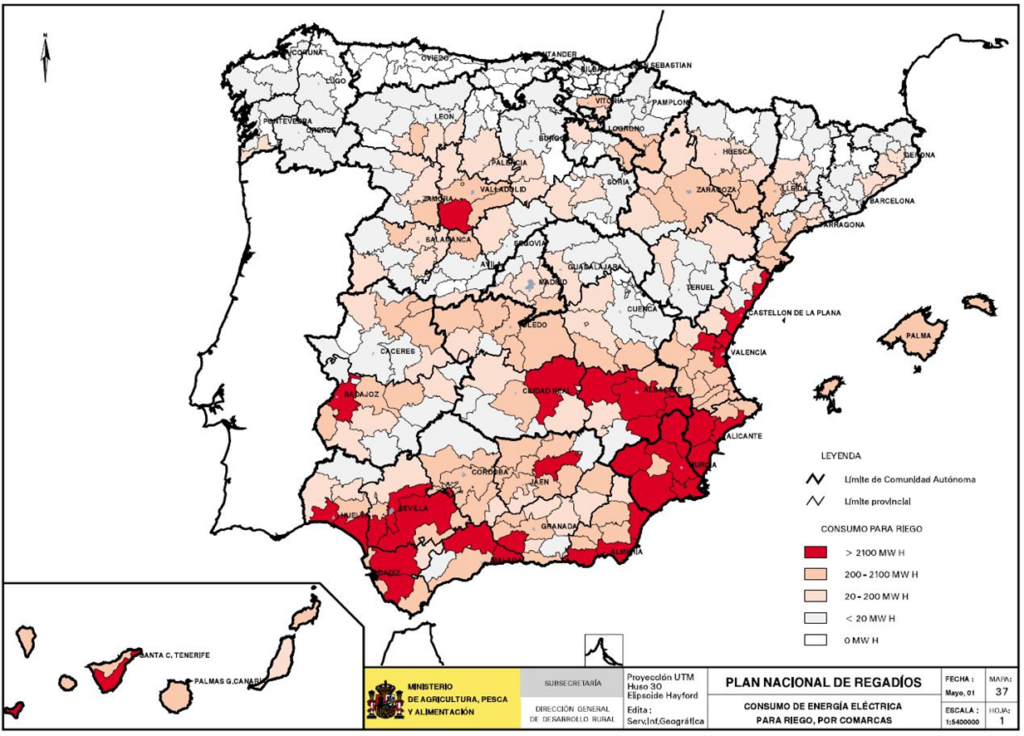

To complete the diagnosis of the situation, in the following sections of chapter 4 an economic analysis of the farms in relation to irrigation is made (4.5), the problems of groundwater are studied (4.6), the distribution of irrigation in the different territorial spaces is analyzed (4.7), the state of the environment in relation to irrigation is summarized (4.8), the consumption and the overall demand of water is studied (4.9) and irrigation is evaluated in light of energy planning (4.10).

- Priorities, objectives and programming

The final step in planning is formalizing the priority of actions within the considered timeframe, determining the objectives to be achieved, and scheduling the necessary administrative procedures, timeline, funding, investments, etc. This is precisely the content of Chapter 5, which in section 5.2 establishes the priority and general objectives, and in section 5.3 specifies the actions, broken down into three types of actions (improvement, irrigation projects underway, and community irrigation projects), duly territorialized, and a support program (training, irrigation system evaluation, environmental monitoring, etc.).

Section 5.4 quantifies and territorializes the investments necessary to achieve the proposed objectives and the planned financing.

Finally, section 5.5 evaluates some of the expected effects of implementing the National Irrigation Plan, such as water consumption and savings, energy effects and the impact on employment.

3 Basic references of the agricultural sector and irrigation

3.1 The physical environment: climate, soil and water

Knowledge of basic resources is essential for any type of planning, and in particular for irrigation.

The physical factors that influence the development of irrigated agriculture are primarily climate, soil, and water. Climate, in terms of sunlight and temperature, determines the types of crops that can be planted and the productivity of irrigated land. Soil is less limiting, since irrigated areas tend to coincide with the best soils, and the area of land suitable for irrigation is much larger than that permitted by water resources and socioeconomic constraints. Water influences the development of irrigated agriculture based on its quality and availability.

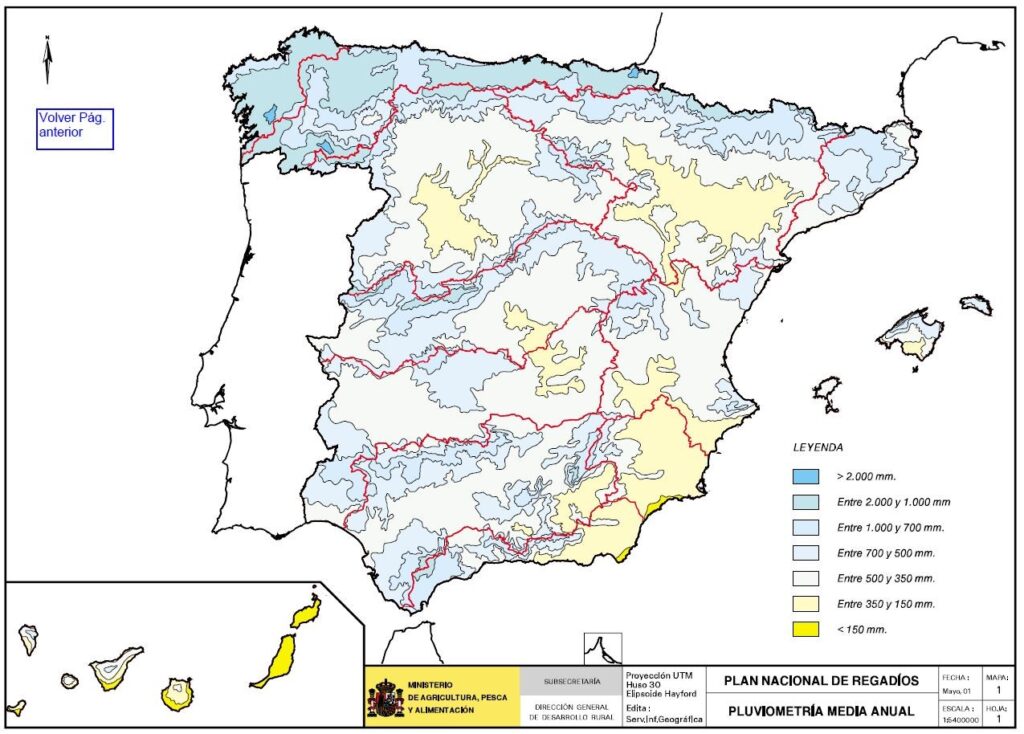

3.1.1 Climate: precipitation and temperatures

The Iberian Peninsula as a whole falls within the temperate Mediterranean climate zone, characterized by cold winters and warm summers, with rainfall concentrated in spring and autumn and drought during the summer months. Despite these general features, there is a wide range of regional climates related to altitude, the complex topography of the territory, and its exposure to Atlantic fronts and Mediterranean influence.

The existence of two distinct zones in the peninsula in terms of rainfall is clear: the "dry Spain" located in the south and the "humid Spain" located in the north.

The "humid Spain" region has average rainfall exceeding 800 mm, occasionally reaching 2,000 mm, and extends across the northern Iberian Peninsula from Girona to A Coruña, associated with the Galician, Cantabrian, and Pyrenean mountain ranges. It corresponds to the Galicia-Costa, Northern, and northern basins, as well as the northern part of the Internal Basins of Catalonia and the northern part of the Ebro basin. In inland areas associated with mountain ranges, humid zones are found amidst considerably drier areas. For example, the highest rainfall on the Iberian Peninsula, with 2,000 mm/year, is found in the Guadalquivir basin, specifically in the Sierra de Grazalema (Western Andalusia). Rainfall exceeding 700–800 mm/year also occurs in the Gredos Mountains, higher elevations of the Iberian System, the Guadarrama Mountains, the Sierra de Gata, the Sierra de Cazorla and Sierra de Segura, and other areas.

"Dry Spain" (400-600 mm) comprises the northern and southern plateaus, the Ebro basin (excluding the Pyrenees), the Levante region, the Guadalquivir basin, the southern basin, and most of the archipelagos. In the southeast and certain inland areas, the driest regions of the peninsula are found, with rainfall below 400 mm and sometimes even less than 200 mm.

The transition from dry to humid Spain takes place along intermediate zones, with rainfall between 600-800 mm, mainly in the foothills of the mountain ranges.

Regarding the seasonality of rainfall, one can differentiate between the Mediterranean regime, with maximums in spring and autumn, which extends mainly through the eastern part of the peninsula, and the oceanic regime, with winter maximums, which extends through the western and Cantabrian areas.

Summer drought occurs throughout the peninsula, although it is more acute in the southern half.

Analysis of temperatures reveals that annual averages exhibit significant variability in their spatial distribution, influenced by altitude and continentality. Regarding temperature fluctuations, the following can be distinguished:

Areas with a marked temperature range encompass the two plateaus and the Ebro Valley. Maritime influence is greatly diminished, and radiation mechanisms result in significant cooling during winter, with temperature inversions in the valleys where cold air accumulates and radiation frosts are frequent. In summer, these same processes cause a strong warming of the surface and the air in contact with it.

Areas along the northern edge and much of the Atlantic coast have mild winters and cool summers as a result of the Atlantic influence that is present throughout the year.

Areas of the Mediterranean coast have warm winters due to the maritime influence and the orographic sheltered position against the cold northern flows, and very hot summers due to the small size of this sea and the frequent inversions of warm air.

3.1.2 Agroclimatic types

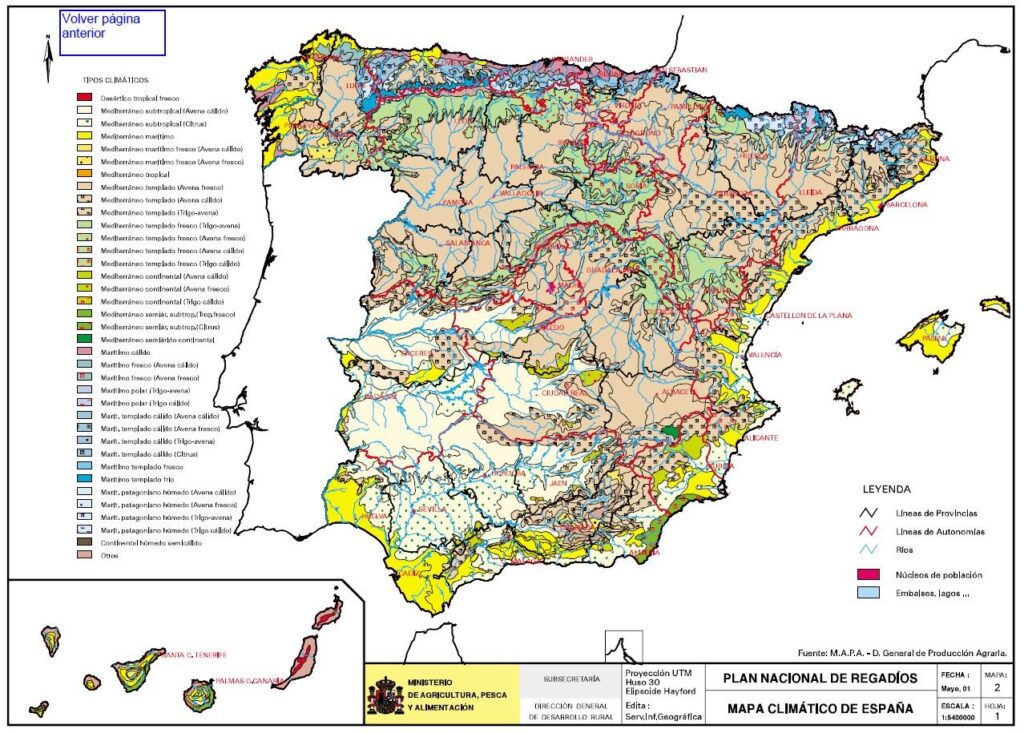

The climatic characterization of the country has been carried out based on the Papadakis agroclimatic classification obtained from the National Agroclimatic Atlas.

The system developed by Papadakis is based on the principle and originality of defining the nature and potential of a climate in terms of the crops that can grow there. To this end, and in accordance with the ecological needs of cultivated plants, it orders them according to their winter and summer temperature requirements, as well as their resistance to frost and drought. This allows for the definition of a zone or season using specific indicator crops whose requirements are known and met within that zone.

He considers that the fundamental characteristics of a climate that affect the development of crops are two: the thermal regime in its two aspects, winter type and summer type, and the humidity regime.

In relation to the major climate types or ecoclimates, the following fundamental groups are represented in Spain: the Mediterranean, which with its various variants occupies the largest surface area, the maritime, the continental and, finally, the desert which is present in a reduced area in the Canary Islands.

In the corresponding chapter dedicated to the characterization and classification of existing irrigation systems, the distribution and location of irrigation systems in the different climatic types predominant in the country are detailed.

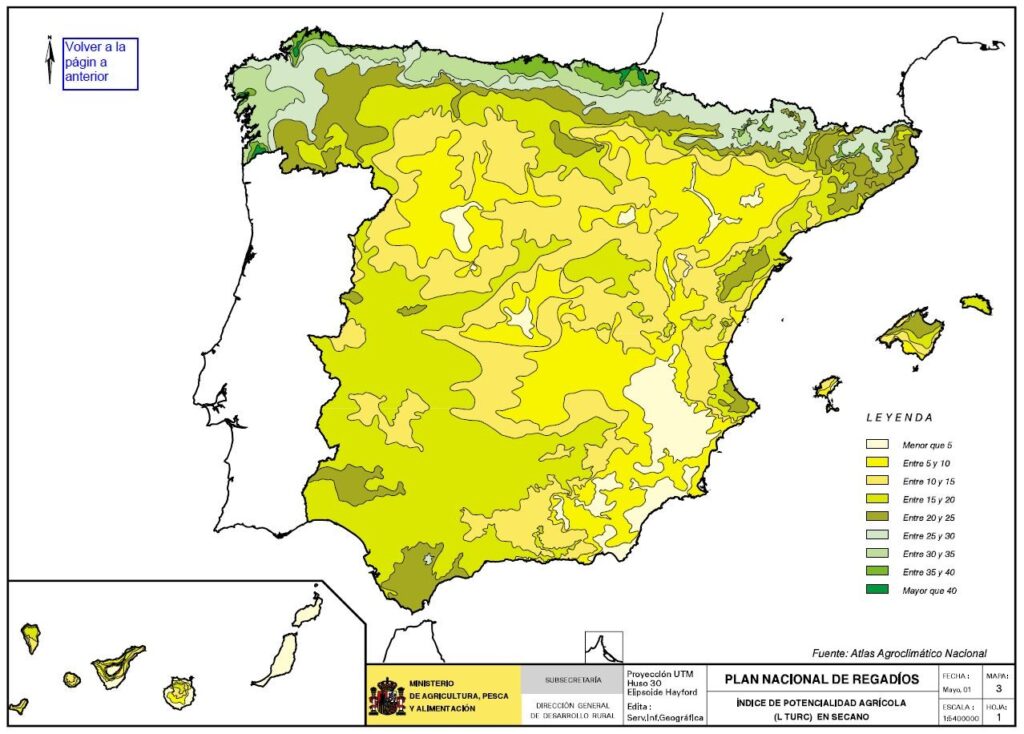

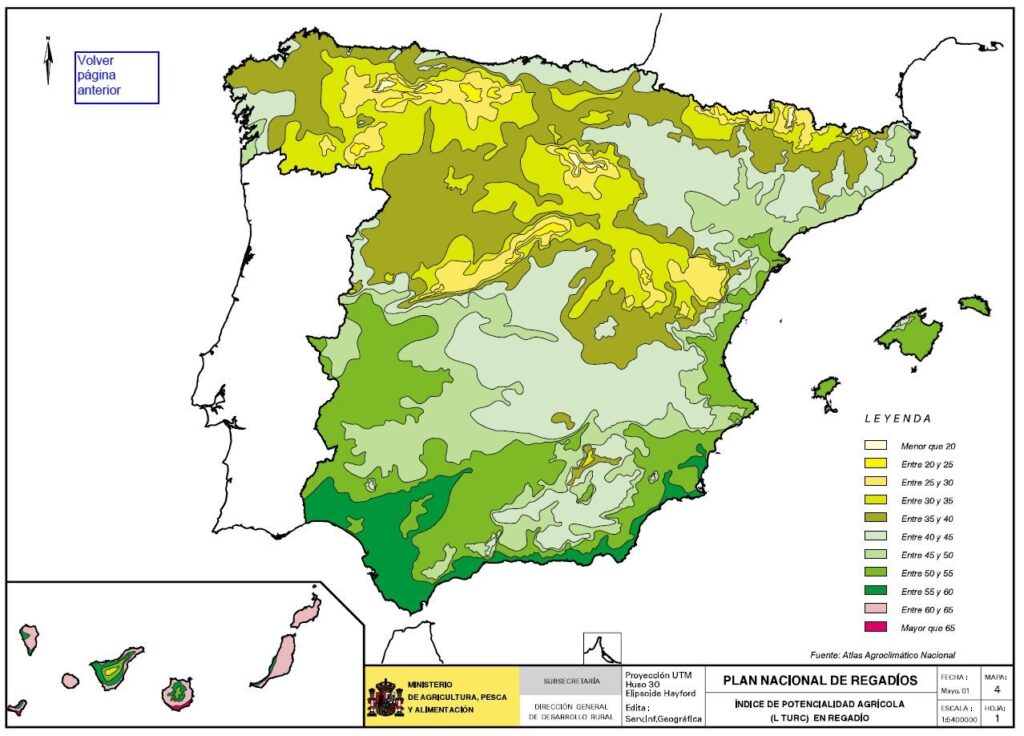

3.1.3 L. Turc's Agricultural Potential Climate Index

Turc's climate index of agricultural potential allows one to establish the productive potential of a territory and to compare this potential between different areas.

The method is based on the existence of a correlation between the values of certain climatic variables, over a given period (a month, a season, a year) and the production, expressed in metric tons of dry matter per hectare, of a plant adapted and cultivated under normal current technical conditions, that is, on well tilled and fertilized soil.

Although the production-index relationship differs for different crops, it is clear that only the numerical value of the index allows for ranking areas according to their higher or lower productive capacity. Within this framework, a distinction will be made between the results obtained under dryland conditions and those obtained under irrigation (assuming that water supply does not act as a limiting factor).

Comparing the annual index for dryland and irrigated land in the same location allows us to establish the overall increase that the transformation to irrigated land represents from a productive point of view in the area considered.

Secondly, once the growing conditions are established, whether dryland or irrigated, the index facilitates the comparison of interzonal productive potentials with respect to a given crop, expressing the differences attributable to any of the climatic factors integrated in its elaboration, in strictly productive terms.

The Turc index for dryland ranges, for the entire national surface, between values below 5 and close to 45. The lowest indices are located in both sub-plateaus and in the southeast and the highest indices in the coastal areas of the Cantabrian and, more specifically, in the Cantabrian-Pyrenean mid-mountain area.

For irrigation, the lowest indices are found in the inland highlands with values close to 15. The maximum potential corresponds to the entire Mediterranean coastal strip and its Atlantic continuation, extended to the Guadalquivir depression, with index values around 60. In this area, the maximum agricultural potential corresponds to the southeast and islands of the Canary archipelago where the value exceeds 60 and in some stations reaches over 65.

3.1.4 The soil

For the general study of land characteristics, the CSIC's 1:1,000,000 soil map, covering the entire national territory, was used. Its units can be converted to their equivalents in other classifications (USDA and FAO Soil Surveys). Land use studies at a scale of 1:100,000 and the crop and land use maps and agro-ecological classifications at a scale of 1:50,000, carried out by the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, were also considered, as were land use studies conducted by the Directorate General for Rural Development in the different river basins. The general characteristics of the land, currently under irrigation and in areas potentially slated for conversion, were also evaluated.

The objective is to provide an overview of current irrigation systems, with their problems due to limitations in their physical parameters, climate, soil and irrigation water, and, on the other hand, to provide an overview of the lands in the different basins for new transformations.

The study by basin shows the high climatic potential of the southwest, south, Mediterranean coast, and archipelagos with soils suitable for irrigation. Even when the soil is not suitable, the creation of artificial soils is a fairly common practice.

It often appears that the soil factor is not the most limiting factor for the implementation of various irrigation systems, with water being more important, both in quality and quantity, and the climate as a determining factor for certain crops.

3.1.5 Water

The water resources of peninsular Spain, with its nearly 500,000 km² surface area, are determined by its topography, climate, and geographical location. The average annual rainfall of 684 mm, equivalent to 346,000 hm³/year, results in an average runoff of 220 mm, providing a volume of natural resources in an average year of 111,000 hm³. Of this, slightly more than 82,000 hm³ are surface water and approximately 29,000 hm³ are groundwater, with roughly 2,000 hm³ corresponding to aquifers that drain directly into the sea.

Of the country's total water resources, only 91% are usable in their natural state, with a uniform demand. This percentage drops to less than 51% for variable irrigation demand, where needs during the dry months significantly exceed those during the wet months. This has necessitated the construction of numerous dams (1,174) with a total reservoir capacity, including smaller ones, of 56,000 hm³, although the available regulated resources are reduced to 43,000 hm³. Not all natural resources could be economically regulated; the potential regulation ceiling is estimated at around 70,000 hm³.

The geographical distribution of water resources is highly uneven. The northern zone, comprising 111% of the Spanish peninsular area, contributes 401% of the resources, but at a high cost for their use. The remaining 891% of the area supplies 601% of the resources, has below-average runoff, and exhibits varying values within it (the Ebro, Duero, Tagus, and Eastern Pyrenees have higher values). Similarly, coverage per capita varies (the Levante coast and the Canary Islands have the lowest rates).

From the perspective of resource management, the national territory is divided into river basins defined in the Water Law as the territory in which waters flow to the sea through a network of secondary channels that converge into a single main channel.

River basins can be inter-community when the territory they comprise belongs to several Autonomous Communities and intra-community when they are included in a single Autonomous Community.

The intercommunity basins are organically dependent on MIMAM, and the intracommunity basins (Galicia Costa, Internal Basins of Catalonia, Balearic Islands and Canary Islands) have been transferred to the respective Autonomous Administrations.

For the purposes of natural resources, watersheds are divided into hydrographic zones and subzones. For the management of available resources, in order to meet water demands, they are divided into exploitation systems and subsystems. A summary of both zoning classifications is shown in the following table.

HYDROGRAPHIC BASINS: SURFACE AREA (km²)2), ZONES AND MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS

| Basin | Area (km2) | Zones (resources) | Management systems | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Zones | Number of Subzones | Number of Systems | Number of Subsystems | |||||||||

| Galicia Coast | 13.916 | 2 | — | — | — | |||||||

| North | 40.813 | 6 | 13 | 28 | 35 | |||||||

| Douro | 78.056 | 5 | 12 | 4 | 12 | |||||||

| Block | 55.769 | 14 | 77 | 5 | 10 | |||||||

| Guadiana | 59.873 | 9 | — | 5 | — | |||||||

| Guadalquivir | 63.085 | 10 | 20 | 15 | — | |||||||

| South | 18.391 | 5 | 16 | 5 | 16 | |||||||

| Safe | 18.631 | 14 | 34 | 1 | — | |||||||

| Júcar | 42.904 | 9 | — | 9 | — | |||||||

| Ebro | 86.098 | — | — | 28 | 32 | |||||||

| Catalonia CI | 16.493 | 3 | 13 | 4 | 9 | |||||||

| Balearics | 4.700 | — | — | 4 | — | |||||||

| Canary Islands | 25.994 | — | — | 16 | 25 | |||||||

3.1.6 Summary

Spanish agriculture operates under more difficult physical conditions than other agricultural systems with which it has to compete.

Extreme temperatures, both in winter and summer, hinder alternative crops or place them in marginal situations.

Rainfall is not only scarce across much of the country, but it is also unevenly distributed throughout the agricultural year. The vulnerability of Spanish agriculture to the physical environment is reflected in the nearly 3.5 million hectares of agronomic fallow land annually; this figure is similar to that of irrigated land, which represents the effort made to, on the one hand, cope with the scarcity of water, an essential element for productive activity, and, on the other hand, take advantage of the favorable sunlight and light conditions of the Mediterranean climate.

The physical diversity of the regions is very high and determines very diverse types of agriculture, with a certain productive specialization, which gives rise in many regions to a great economic and social dependence on a specific crop (olive groves and vineyards, for example).

3.2 Demographics and working population

3.2.1 Introduction

In studies of economic development problems, the demographic conditions of territories affected by growth processes are considered a critical factor for the success of any programs or measures that may be conceived, whether we are talking about development strategies embedded in a plan or about more spontaneous, endogenous initiatives. In both cases, the sustainability of investments depends very essentially on the human resources committed to the project.

Implementation of irrigation involves one of the rural development measures with the strongest territorial impact, clearly affecting the populations concerned, modifying population expectations in the immediate term and opening up other expectations with long-term repercussions.

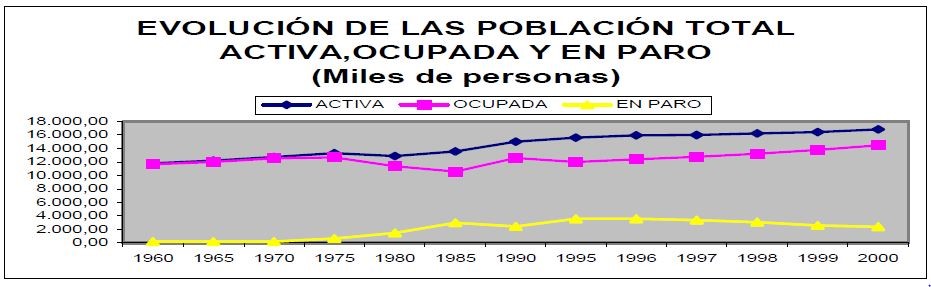

A category that is both demographic and economic is the fraction of the total population that can engage in economic activity, that is, those who actively participate in economic life. The evolution of the active population, as well as its structure and distribution across the territory, provides a measure of productive potential, of the employment capacity that can be effectively mobilized by a development initiative such as the irrigation of an area or region.

Demographic potential and labor potential shape the framework of development programs that consider the territorial resonance of their action programs.

Within the framework of irrigation planning, which by its very nature has a direct impact on the territory, it is necessary to consider the following significant headings: Evolution and annual growth or regression rates of the population and territorial distribution of the population, the evolution of the agricultural population and its relationships with the activity as a whole as well as its relationships with the transformation into irrigated land.

3.2.2 Evolution in the Spanish population

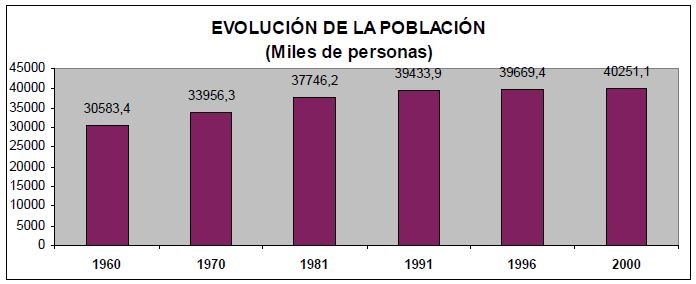

The Spanish population has evolved differently than in neighboring countries, in a context of higher growth rates for Spain. However, in recent years this growth pattern has changed, representing a shift in trend. Currently, the Spanish population growth rate is comparable to that of the EU and even slightly lower if immigration is excluded.

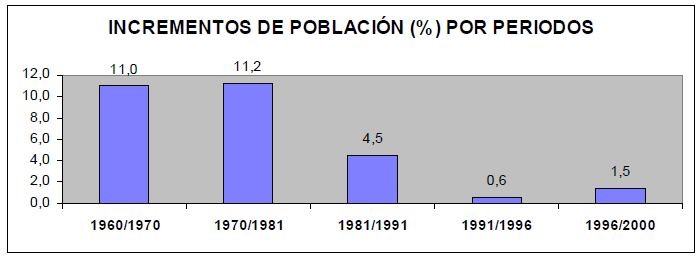

The Spanish population has increased from 30,583,466 inhabitants in 1960 to 40,251,100 inhabitants in 2000. However, the population has evolved towards a decrease in growth rates, which have gone from 1.011% per year between 1960 and 1981 to 0.44% per year between 1981 and 1991, continuing its negative evolution between 1991 and 1996 when it reached 1.5% per year.

In the last period analyzed there has been some recovery of this regressive trend, caused mainly by the growth of immigration, which however does not prevent the estimates of growth rates from being negative from the year 2011 onwards, if the current demographic trends are maintained and in the absence of migratory movements.

Viewed as a whole, the Spanish population has evolved as shown by the following indicators, which clearly express a process of approximation to the demographic parameters of all European countries.

DEMOGRAPHIC INDICATORS

| Indicators | 1960 | 1970 | 1981 | 1991 | 1996 | 1998 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude Birth Rate (‰) | 21,6 | 19,5 | 14,1 | 10,1 | 9,23 | 9,37 |

| Crude Mortality Rate (‰) | 8,7 | 8,3 | 7,8 | 8,6 | 8,95 | 8,88 |

| Vegetative Growth (‰) | 12,9 | 11,2 | 6,3 | 1,5 | 0,28 | 0,49 |

| Life expectancy at birth (years) | 69,8 | 72,3 | 75,6 | 76,9 | 78,3 | * |

| Survival Rate > 65 years (number per 100,000) | 74,5 | 78,1 | 82,4 | 84,1 | 85,8 | * |

The demographic change that has occurred in Spain in the last forty years has meant a fall in the gross birth rate of 12.2 points (from 21.6 to 9.4 births per thousand inhabitants) while the mortality rate has remained stable, which has led to a strong aging process, with effects of different intensity depending on the degree of rurality of the population centers.

Both the growth in life expectancy at birth, which has experienced an increase of 8.5 years in the period 1960-1996, and the survival rate of the population over 65 years of age, which has grown by 11.3 points, clearly express the conditions of foreseeable evolution of the population and its foreseeable repercussions on the structure of social services.

There has been a trend in the rates of natural growth towards demographic stagnation, going from an annual population contribution of 12.9‰ to the incorporation of less than half a point in 1998. (0.49‰).

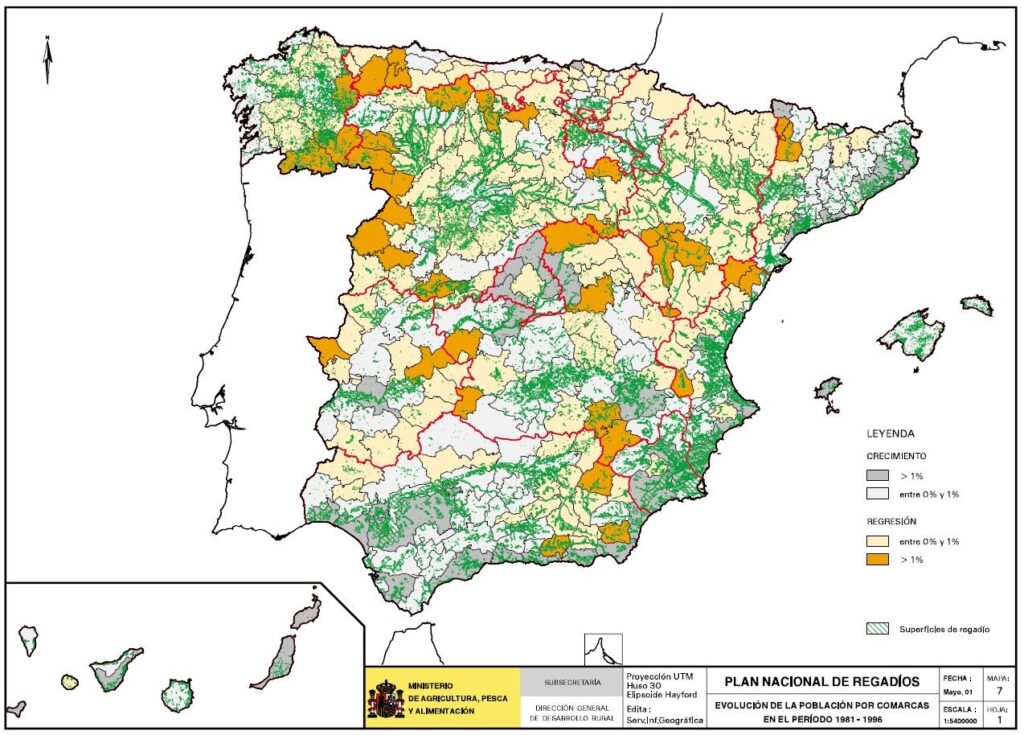

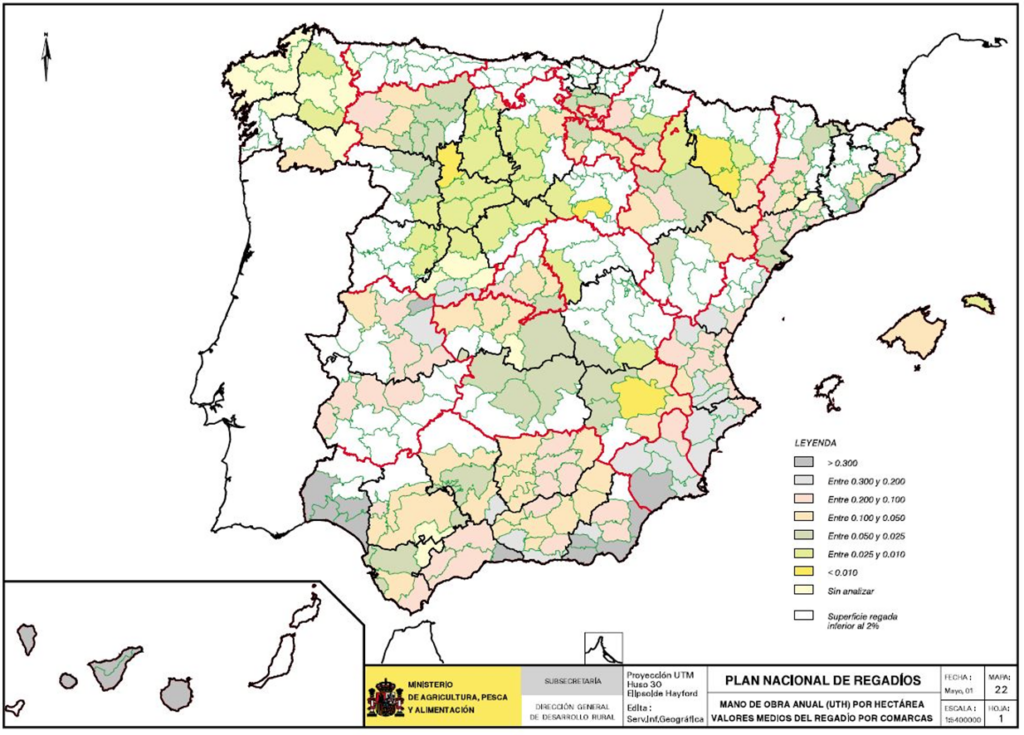

Beyond the global perspective considered above, map no. 7 shows the evolution of the Spanish population on the territorial basis that constitutes the agricultural regionalization prepared by the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food and published in 1996, which is considered the most appropriate to relate to the irrigated areas.

The cumulative annual population growth rates at the district level between 1981 and 1996 (or their negative values: demographic decline) allow us to observe its evolution and highlight the trend toward depopulation of inland districts, with a steady transfer of population to coastal regions and large urban areas. The trend at the district level refers to 1996, as it is the last year for which official population register data is available until the next population census in October 2001.

The population loss during the period 1981-1996 is clearly evident in the districts covering the territory known as inland Lusitania, extending to the irrigated area of the Lower Guadiana Valley. In this area, a demographic recovery occurred and continued southward to the irrigated area of the Chanza River. Many mountainous districts of the Central, Iberian, and Betic Systems are experiencing severe depopulation, all of which have very little irrigated land, with the exception of some older irrigated areas (such as El Rosarito).

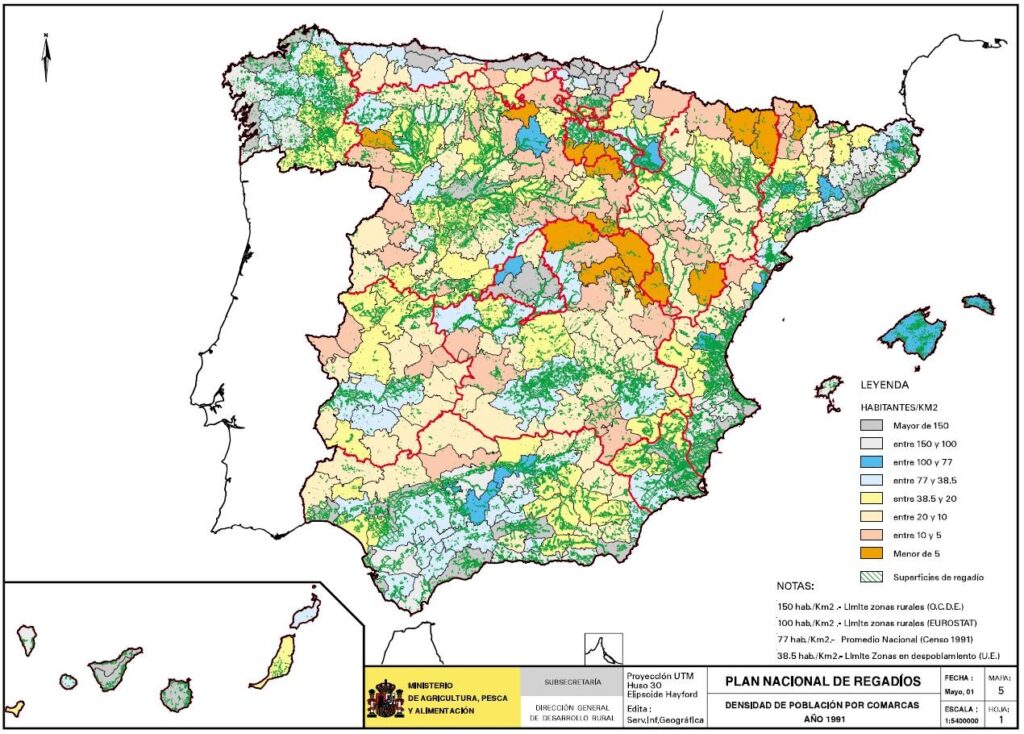

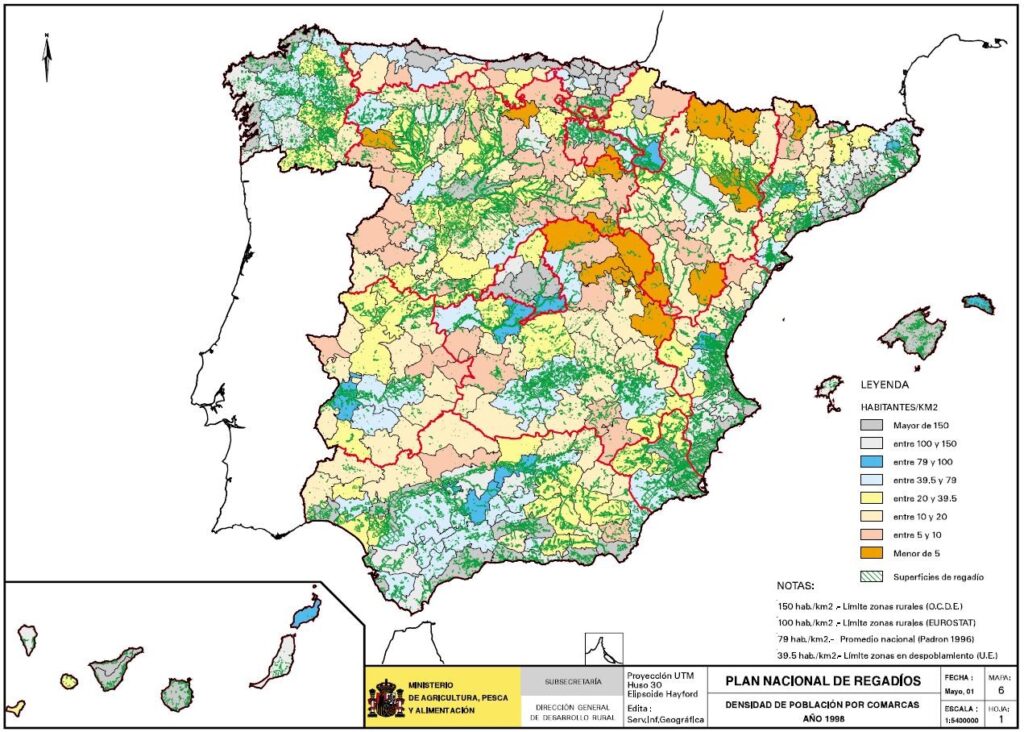

Comparing population densities between the two periods mentioned allows for a more nuanced understanding of the information provided regarding the evolution of annual population growth rates by relating population to the territory occupied. Maps nyou Figures 5 and 6 reflect the regional population densities of the years 1991 (Census) and 1996 (Register), establishing four recognized categories of rurality limits: The first, according to the Commission's criteria (Directive 466/86/EEC), sets the population limit for disadvantaged areas at 50% of the national average density, which is why the interval in which the average density of Spain is found is different in each map (77 inhabitants per km2 in 1991 and 79 in 1996).

The maps incorporate the rurality limits according to Eurostat and the OECD respectively, located at 100 and 150 inhabitants/km²2 which have been widely used by their respective bodies for the formulation of their territorial strategies or their studies and reports.

The maps show the regions with the most serious depopulation problems (regions with population densities of less than 10 inhabitants/km²).2 ) in the profiles of the mountain systems, although the threat to the central system and the Rioja mountain ranges and some areas of the cereal-growing plateau of Castile and León should be emphasized. The series of districts that make up inland Lusitania, which do not have the support of irrigated agriculture, are also within the threatened areas, with population densities of less than 20 inhabitants/km².2 which can be considered as the upper limit of the threatened areas.

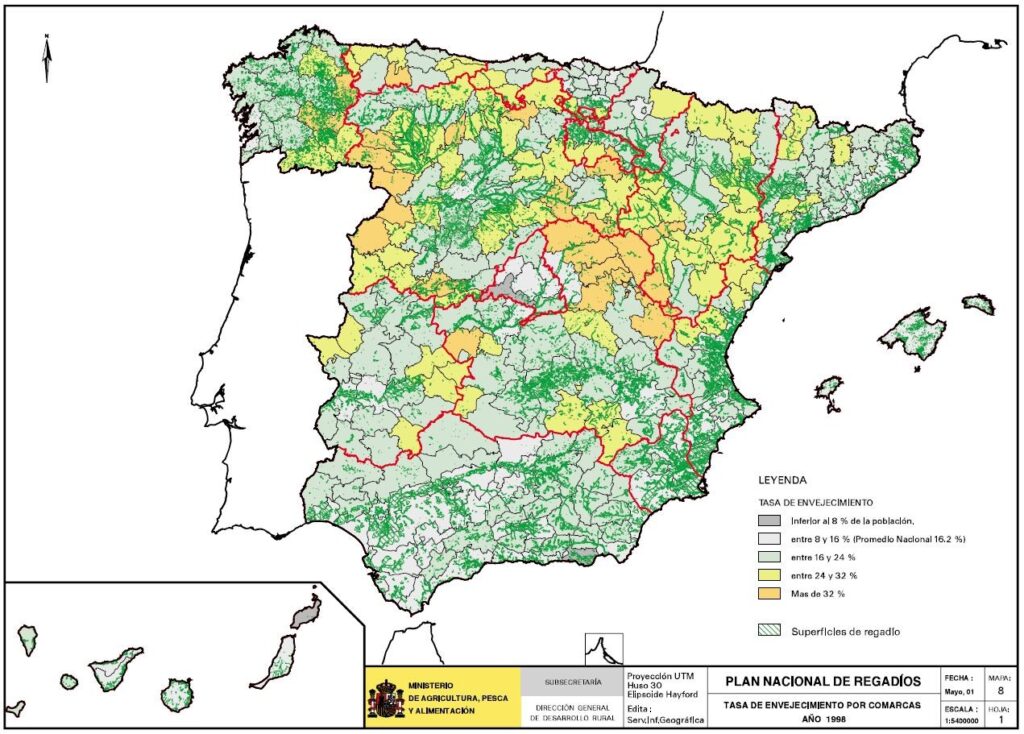

Map 8 details the uneven distribution of the population from the perspective of the proportion of people of retirement age, which is concentrated in areas that have suffered the most severe demographic erosion, resulting in lower population densities. These areas are therefore simultaneously older and more depopulated, reaching levels of serious decline in mountainous regions. Both Castiles show significant signs of aging, mitigated by the presence of irrigated areas in some districts, a phenomenon also observed in the Ebro Valley. The areas with the least aging cover only the portion of the territory in the coastal districts of the Mediterranean and South Atlantic arcs where the greatest territorial complexity coincides with metropolitan areas, areas of great tourist importance, and irrigated areas of significant economic importance. The Guadalquivir basin presents a unique case in this territorial distribution, possibly attributable to the demographic vitality of that region.

3.2.3 Population evolution in rural areas

The European Union has established in its structural action policy a definition of rural space that does not imply a simple geographical delimitation but refers to the economic and social fabric that encompasses diverse activities and includes natural and cultivated spaces, as well as villages, towns, small cities and regional centers. (Future of the Rural World, 1988, 39) This definition, covering a very large territory (more than 80% of the surface area of the European Union), has required more operational definitions based on population density or the number of inhabitants.

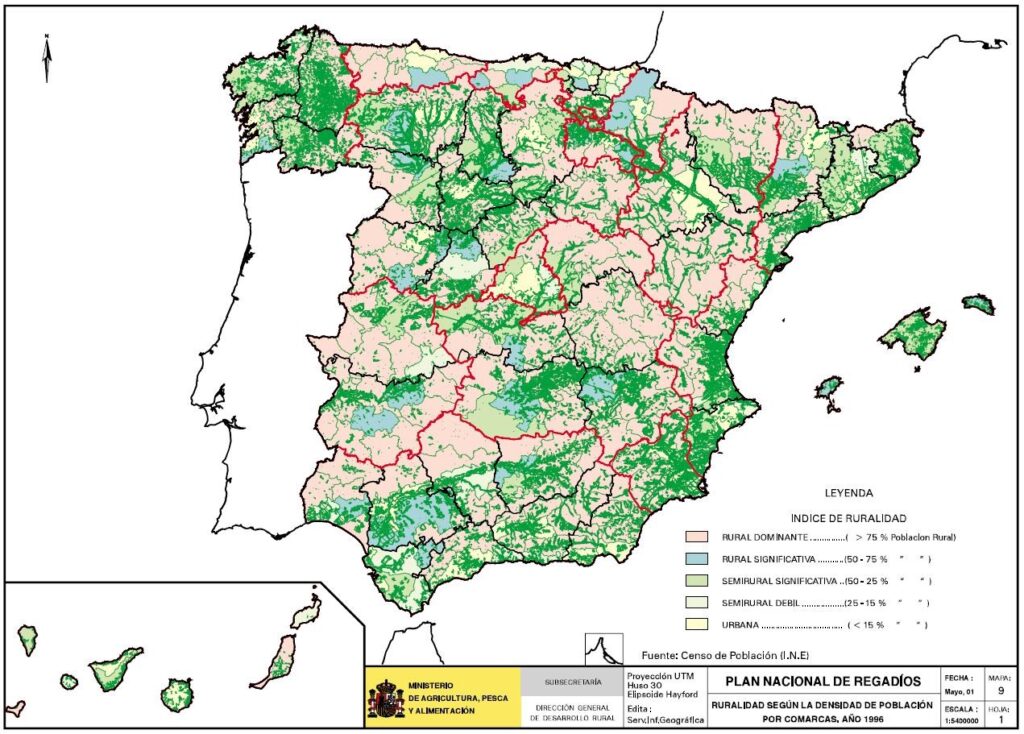

One of the most used variables for assessing the degree of rurality in successive community initiatives related to rural areas is population density. Map No. 9, which details the degree of rurality of Spanish regions, is presented based on the proportion of municipalities with rural densities, according to community regulations, considering the density limit at 120 inhabitants per km².2. In accordance with the provisions of the Community Initiatives, this map allows for the linking of rural municipalities and urban structures within Spanish regions, acknowledging that every region contains some degree of rurality. The map thus details a gradient of rurality that facilitates a typology.

From a census point of view, the data from the Register in 1999 in Spain showed a population of 40,202,760 inhabitants, of which 51% lived in municipalities with more than 50,000 inhabitants and 15.4% in municipalities with less than 5,000 inhabitants, as detailed in the attached table.

POPULATION IN THE MUNICIPAL ENTITIES IN 1999

| | Less than 5,000 | From 5,000 to 10,000 | From 10,000 to 20,000 | From 20,000 to 50,000 | Of more than 50,000 | SPAIN | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Population in 1999 | 6.174.909 | 15,4 | 3.517.474 | 8,7 | 4.611.424 | 11,5 | 5.415.173 | 13,5 | 20.483.780 | 51,0 | 40.202.760 | 100 |

In the period from the 1960 census to 1996, there was a complete transformation of the territorial distribution of the population, resulting in a 47.1% decrease in the population residing in settlements with fewer than 5,000 inhabitants and a 46.3% increase in the population of cities with more than 50,000 inhabitants. In other words, the number of municipalities with more than 50,000 inhabitants existing in 1960 increased by 59.5%. The following table details the population trends in each census period. The table allows us to appreciate the sharp trend towards rural depopulation, for which the calculation of the variation of the rural or semi-rural population (the singular entities of less than 10,000 inhabitants, according to the INE) and the populations in population aggregates of more than ten thousand, more than twenty thousand and more than 50,000 has been reiterated, in which we understand the scope of the definition of community rurality concludes.

VARYoA.C.YoÓN OF THE POPULATION (%) OF THE NUCLEI ACCORDING TO THEIR SIZE

| Period | Less than 5,000 | From 5,000 to 10,000 | Greater than 10,000 | Over 20,000 | Over 50,000 | SPAIN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1960/96 | -47,1 | 37,5 | 40,9 | 45,5 | 46,3 | 29,5 |

| 1970/96 | -22,1 | 22,4 | 23,8 | 26,3 | 26,1 | 16,7 |

| 1981/96 | -6,8 | 7,8 | 7,8 | 6,8 | 4 | 5,1 |

| 1991/96 | -1,3 | 3,3 | 2,6 | 1,6 | 1,1 | 0,6 |

From a territorial point of view, this has led to the formation of large metropolitan areas that cover extensive territories, with the emergence of peri-urban agriculture in significant proportions in those regions where agriculture and conurbations coexist, determining the interaction between several large cities within a regional space.

Settlement has evolved in a way that is consistent with the redistribution of the population, and two periods can be identified in the recent distribution of population and habitat:

During the period from 1981 to 1991, while 57.9% of municipalities with fewer than 2,000 inhabitants lost more than 10% of their population and 13.2% grew above the national average, only 25.6% of intermediate-sized municipalities (2,000 to 5,000 inhabitants) experienced losses exceeding 10%. However, in these municipalities, 27.7% grew above the national average for their group, demonstrating an irregular trend across the country. For municipalities with more than 5,000 inhabitants, the proportion of growing population centers is greater than the proportion of those losing population, thus highlighting both population restructuring mechanisms and the trend toward demographic concentration starting from the most rural areas.

EVOLUTION OF HABITAT STRUCTURE IN THE PERIOD 1981-1991

| Municipalities by number of inhabitants | Growing municipalities | Municipalities in decline | Totals | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth above the national average | Growth between the final average. and 0 | Decrease between 0 and 10 % | Decrease greater than 10 % | ||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | ||

| < 2,000 | 770 | 13,2 | 238 | 4,1 | 1.446 | 24,8 | 3.371 | 57,9 | 5.825 |

| 2,000 to 5,000 | 303 | 27,7 | 115 | 10,5 | 396 | 36,2 | 280 | 25,6 | 1.094 |

| 5,000 to 10,000 | 229 | 42,3 | 66 | 12,2 | 157 | 29,0 | 89 | 16,5 | 541 |

| 10,000 to 20,000 | 183 | 57,2 | 57 | 17,8 | 57 | 17,8 | 23 | 7,2 | 320 |

| 20,000 to 50,000 | 112 | 63,6 | 30 | 17,0 | 27 | 15,3 | 7 | 4,0 | 176 |

| > 50,000 | 70 | 57,9 | 18 | 14,9 | 28 | 23,1 | 5 | 4,1 | 121 |

| Spain | 1.667 | 20,6 | 524 | 6,5 | 2.111 | 26,1 | 3.775 | 46,7 | 8.077 |

Population losses during the period 1981-1991 in the centers with fewer than 2,000 inhabitants, that is, the most rural ones, are distributed between the two Castiles and Aragon (48 % of the total of the municipalities that have lost more than 10 % of their population) these Autonomous Communities are at the same time the ones that have the most important number of municipalities in this category (44.2 % of the total of municipalities with less than 2,000 inhabitants).

EVOLUTION OF HABITAT STRUCTURE IN THE PERIOD 1991-1999

| Municipalities by number of inhabitants | Growing municipalities | Municipalities in decline | Totals | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth above the national average | Growth between the final average. and 0 | Decrease between 0 and 10 % | Decrease greater than 10 % | ||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | ||

| < 2,000 | 1.182 | 19,9 | 401 | 6,7 | 2.072 | 34,8 | 2.291 | 38,5 | 5.946 |

| 2,000 to 5,000 | 344 | 34,1 | 156 | 15,5 | 417 | 41,4 | 91 | 9,0 | 1008 |

| 5,000 to 10,000 | 238 | 46,3 | 98 | 19,1 | 155 | 30,2 | 23 | 4,5 | 514 |

| 10,000 to 20,000 | 202 | 61,2 | 55 | 16,7 | 68 | 20,6 | 5 | 1,5 | 330 |

| 20,000 to 50,000 | 127 | 68,6 | 29 | 15,7 | 12 | 6,5 | 17 | 9,2 | 185 |

| > 50,000 | 57 | 48,3 | 28 | 23,7 | 33 | 28,0 | 0 | 0,0 | 118 |

| Spain | 2.150 | 26,5 | 767 | 9,5 | 2.757 | 34,0 | 2.427 | 30,0 | 8.101 |

During the period 1991–1999, 38.5% of municipalities with fewer than 2,000 inhabitants lost more than 10% of their population, while 19.9% of this same group grew above the national average, halving the population decline trend in small rural municipalities (one municipality grew for every two that declined in 1999, compared to the ratio of one for every four in the previous period). Intermediate-sized municipalities showed a similar pattern, with 34.1% of the cohort growing and only 9% of this group losing population at rates exceeding 10%, whereas in the previous decade the relationship between growth and loss was practically equal. For municipalities with more than 5,000 inhabitants, the proportion of population centers growing above the national average is greater than that of those losing population, a situation consistent with that of the previous period. Likewise, compared to the previous decade and to municipalities with more than 10,000 inhabitants, there is a noticeable increase in the percentage of municipalities losing population exceeding 10%.

3.2.4 Population evolution and irrigation

The impact of irrigation on demographic trends is undeniable, although the patterns of influence are by no means linear. In general, regions with irrigated land maintain higher population densities and positive annual growth rates; where population decline occurs, the rate of emigration is slower than in areas without irrigation.

In the case of the regions of the Atlantic-Mediterranean coastal strip (see maps 5 and 6) which accumulate some of the areas with the highest population densities and surface area with long-standing irrigation and ample supply, several growth factors come together, that is, they grow both because of internal migration and their own development potential.

Compare the cumulative annual growth rate of Spain (0.33 % annually between 1981 and 1996) with those corresponding to the set of these regions (above 1 % annually) as detailed in map no. 7.

Regarding inland irrigation, the relationship between population growth and irrigation is equally evident, although more nuanced. The Ebro and Guadalquivir basins stand out for the convergence between irrigated areas and higher population densities, especially in the upper Ebro, the Guadiana plains, and the districts of Campo de Calatrava, La Mancha, and Central Albacete, which exhibit a territorial condition that could be described as "demographic islands" given the surrounding low population density.

The irrigated areas of the Duero and Tagus river basins exhibit a less clear demographic pattern. In a climatic context that does not allow for explosive variations in productivity due to irrigation, the function of irrigation, from a population perspective, lies in mitigating migratory pressure, thus maintaining a population level that sustains territorial viability, which would be problematic without it. Maps 5 and 6 show how the areas surrounding the districts with irrigated zones along the Duero are generally below the population levels corresponding to irrigated areas. In short, while in other areas irrigation is a measure of rural development, in these districts it can be understood as a measure to support rural development.

Taken together, the population in the different regions with irrigated areas shows the following evolution:

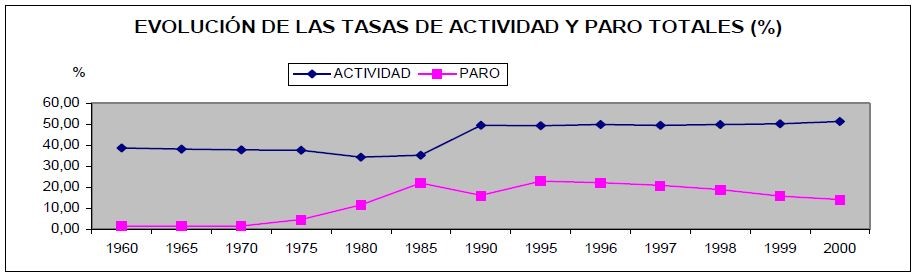

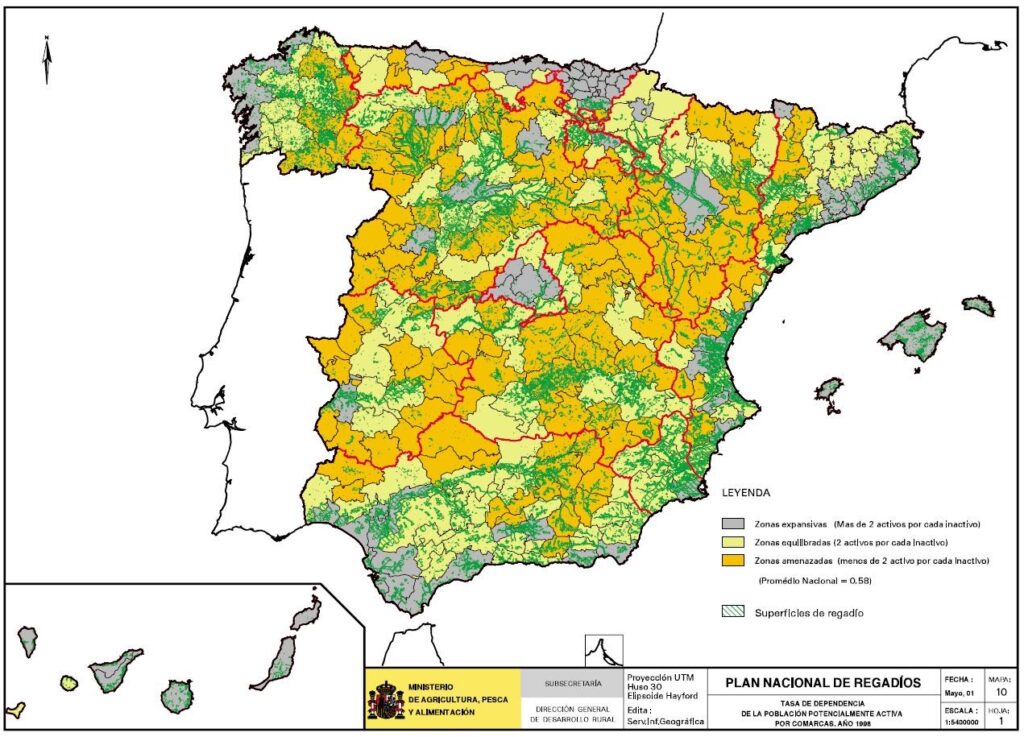

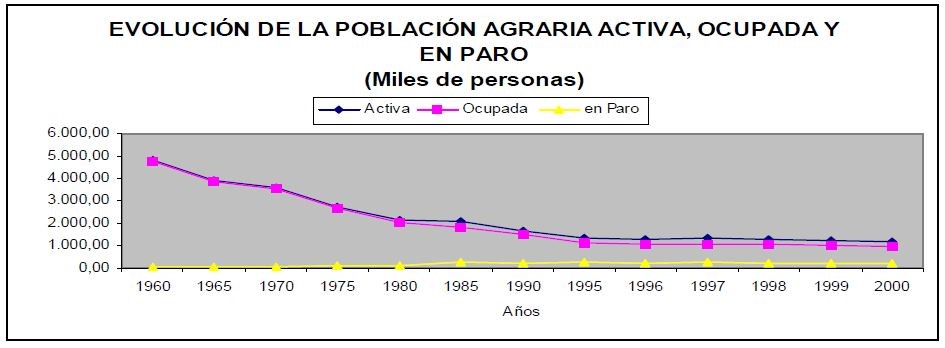

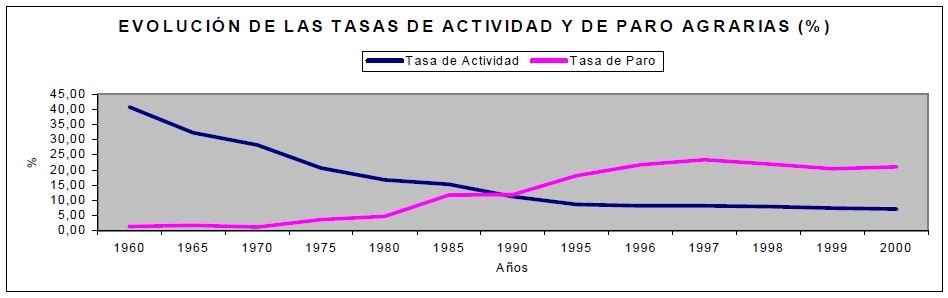

POPULATION EVOLUTION IN IRRIGATED AREAS (%)